For most of 2024, mid-training was the part of the pipeline nobody openly talked about (although already practical explorations within frontier labs). It was the quiet phase between the glamour of pre-training at scale and the excitement of RLHF breakthroughs. Then, in the span of six months, three things happened: two survey papers formalized it as a research discipline, a CMU study proved it outperforms RL-only under fixed compute, and a Shanghai team showed that RL can reach backward to improve mid-training itself. Mid-training went from engineering plumbing to the most strategically important stage of the pipeline.

The standard recipe is well known: pre-train on trillions of tokens, fine-tune on high-quality instructions, then apply RLHF or GRPO to align the model. Mid-training — the phase between pre-training and supervised fine-tuning where you continue training on domain-specific data — was typically treated as an optional engineering step. Something Qwen did for code, something Meta did for long context, something NVIDIA did for domain adaptation. Useful, yes. Interesting, not particularly.

I say this from firsthand experience. In 2024, I spent half a year at a frontier lab working on continued pre-training for the Seed foundation models — curating StackExchange and CommitPack data, running ablation experiments on 1.3B and later 3.3B proxy models, gathering insights, and iterating on data mixing ratios before the annealing stage. At the time, mid-training was very much an engineering exercise: get the data pipeline right, tune the learning rate schedule, verify that general capabilities didn’t degrade. Important work, but not the kind that generated research papers or conference talks. The title “Re-visiting” is literal — I’m returning to a stage of the pipeline I once worked on daily, and finding it transformed.

That changed in the second half of 2025.

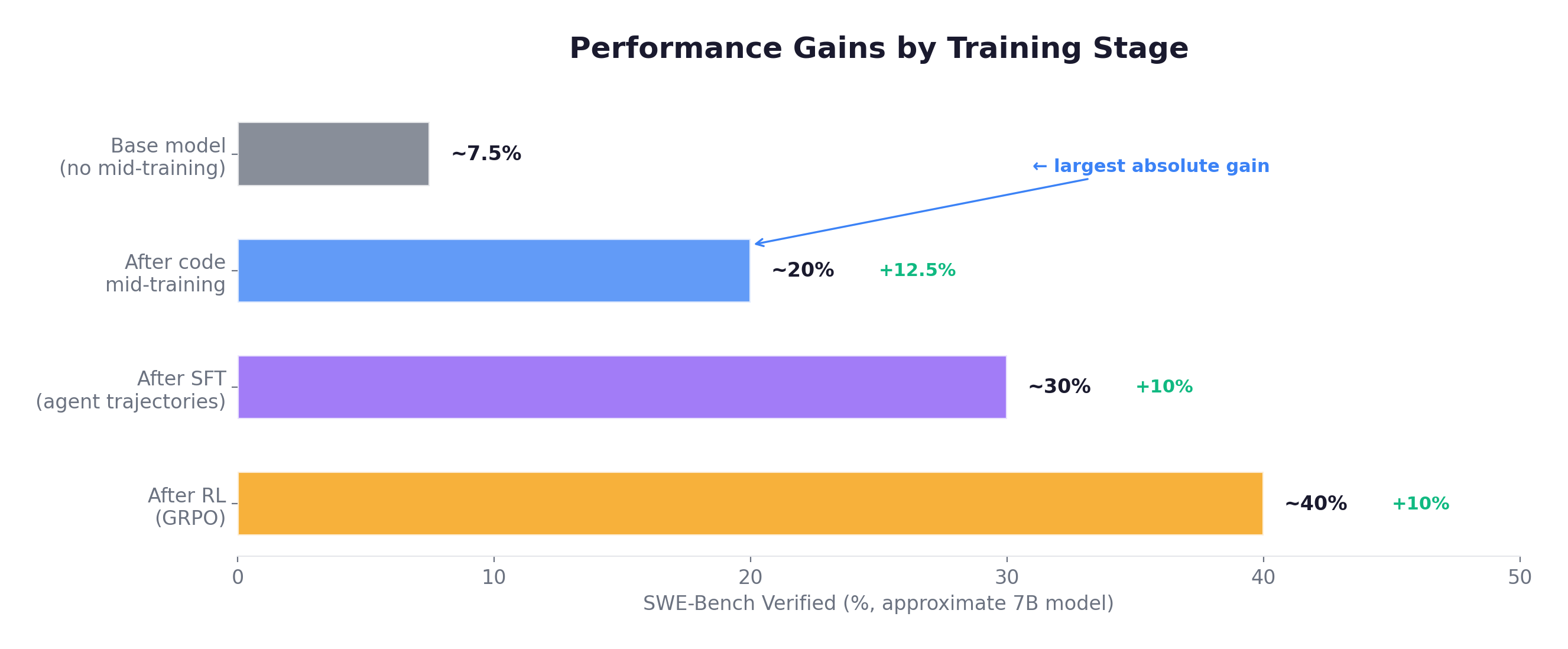

Between October 2025 and February 2026, the field produced a burst of research that fundamentally repositioned mid-training in the pipeline. Two survey papers (Gao et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2025) simultaneously formalized mid-training as a distinct research area. NVIDIA demonstrated that reasoning data injected during pre-training creates a compounding advantage that widens through subsequent training stages — challenging the assumption that reasoning is purely a post-training concern (Akter et al., 2025). CMU ran controlled experiments proving that mid-training outperforms RL-only allocation under fixed compute budgets by over 10% on out-of-distribution tasks (Zhang et al., 2025). And in February 2026, the ReMiT paper broke the cardinal rule of the linear pipeline: it used an RL-trained model’s reasoning priors to retroactively improve mid-training data weighting, creating a self-reinforcing flywheel (Huang et al., 2026).

Meanwhile, the practical impact became undeniable. Qwen3-Coder-Next — an 80B-total/3B-active MoE model — achieved 71.3% on SWE-Bench Verified and 44.3% on the harder SWE-Bench Pro, competitive with models 10-30x its active parameter count. Its secret? A massive mid-training phase with 600B tokens of repository-level code, multi-scaffold agentic trajectories, and 800K synthesized software engineering tasks. SWE-smith demonstrated that 50,000 training instances could be manufactured from 128 GitHub repositories with just 20 hours of human labor and $1,360 in compute, achieving 40.2% on SWE-Bench Verified with rejection sampling alone — no RL required.

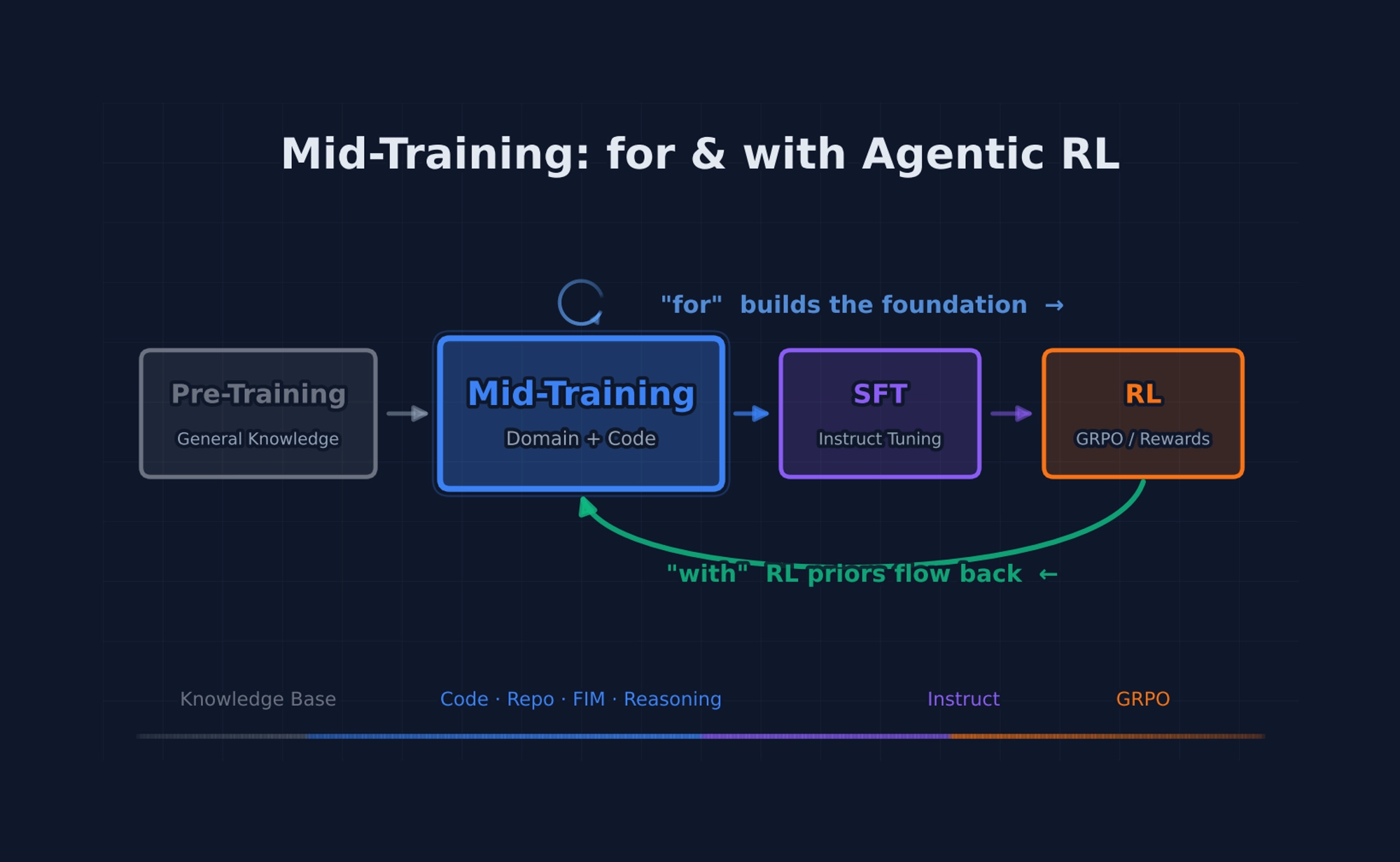

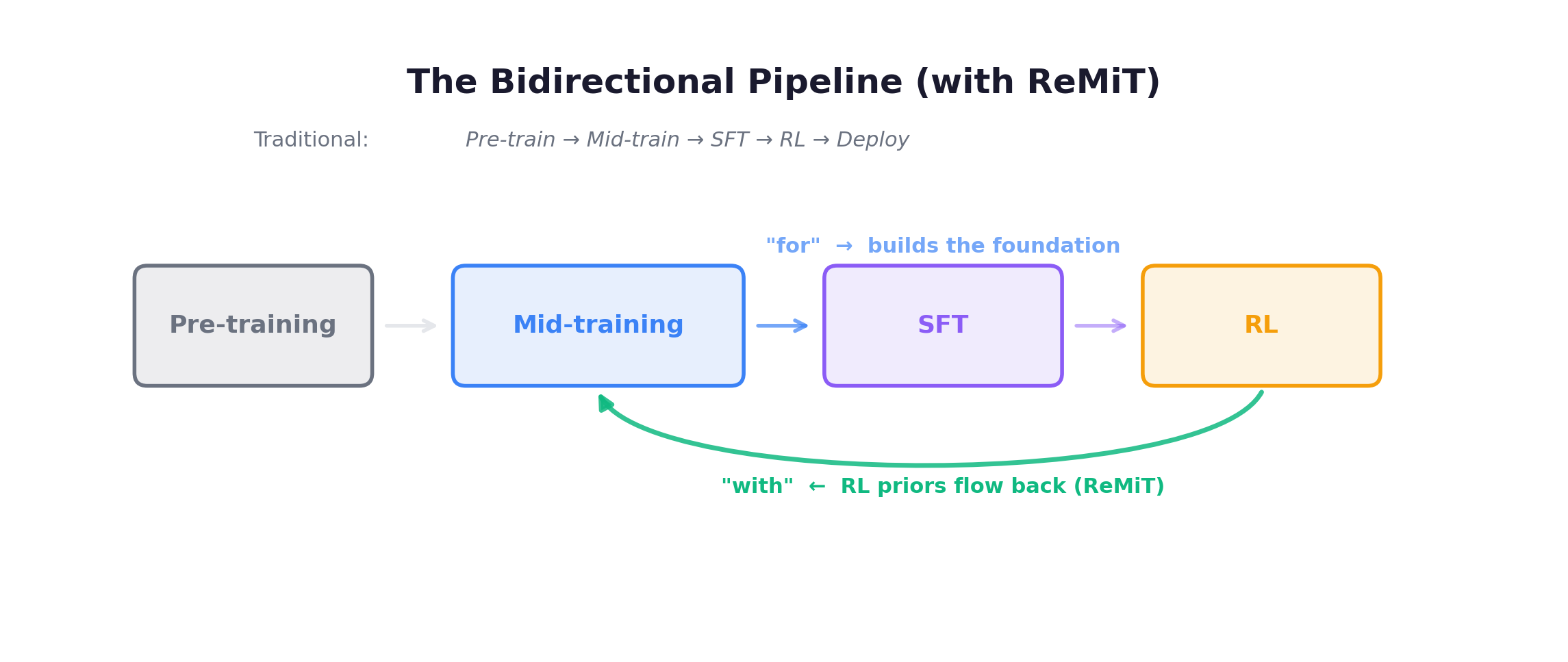

The “For & With” Framing

This post examines mid-training through a dual lens:

Mid-training for agentic RL — the traditional view. Mid-training builds the knowledge foundation that RL later exploits. It teaches code understanding, tool-use formats, repository structure, and debugging patterns. Without it, RL faces a brutal cold-start problem: the model wastes its RL budget learning what actions exist instead of optimizing when to take them. DeepSeek’s R1-Zero experiment showed that RL can induce reasoning from scratch — but only when the base model has sufficient knowledge. Mid-training is what makes the base sufficient.

Mid-training with agentic RL — the emerging view. The pipeline is no longer unidirectional. RL signals can flow backward to improve mid-training itself. ReMiT demonstrates that an RL model’s token-level probability gaps can serve as weights for mid-training’s next-token prediction loss, upweighting “pivotal” reasoning tokens. NVIDIA’s RLP shows that RL can be embedded within the pre-training/mid-training objective as a dense reward signal. The linear pipeline is becoming a loop.

The post starts with fundamentals (Section 1), then builds the case for why mid-training sets the ceiling for agentic RL (Sections 2-3), examines data synthesis at scale (Section 4), and dives into three papers that reshape how we understand mid-training’s interaction with RL (Sections 5-7). It closes with Qwen3-Coder-Next as a case study (Section 8) and a practical recipe (Section 9).

1. Mid-Training 101

What Is Mid-Training?

Mid-training (also called continual pre-training, domain-adaptive pre-training, or simply CPT) is a training phase inserted between general pre-training and supervised fine-tuning. The model continues autoregressive next-token prediction, but on a curated, domain-shifted data mixture — typically 0.1–5.5T tokens with much higher concentrations of code, math, reasoning traces, or other target-domain data than the original pre-training corpus (which is typically 2–18T tokens of general web data).

What separates mid-training from simply “more pre-training” is intentional distributional shift. Pre-training aims for broad coverage; mid-training strategically overweights specific capabilities while carefully preserving general ones. The learning rate is typically 3-10x lower than the pre-training peak (e.g., 2e-5 vs 1e-4), with gentle warmup to avoid catastrophic forgetting.

Disambiguating “Mid-Training” — A Term Used Differently Across Labs

Before going further, it’s worth clarifying a source of confusion: different organizations use “mid-training” to mean different things.

The broad definition treats mid-training as synonymous with continued pre-training (CPT) — any training phase between initial pre-training and SFT that continues the next-token prediction objective on domain-shifted data. Under this definition, Code Llama’s 500B-token code specialization and Qwen-Coder’s 5.5T-token code CPT are both “mid-training.”

The narrow definition, increasingly common in practice, reserves “mid-training” (or “Stage 2.5”) specifically for a structured pre-training phase that sits between raw-code CPT and traditional SFT. This phase uses chat-formatted data, loss masking, and high-quality synthetic data — but at pre-training scale (tens to hundreds of billions of tokens), not SFT scale (millions of samples). The key distinction: it looks like SFT in format but operates at CPT scale and teaches capability, not style.

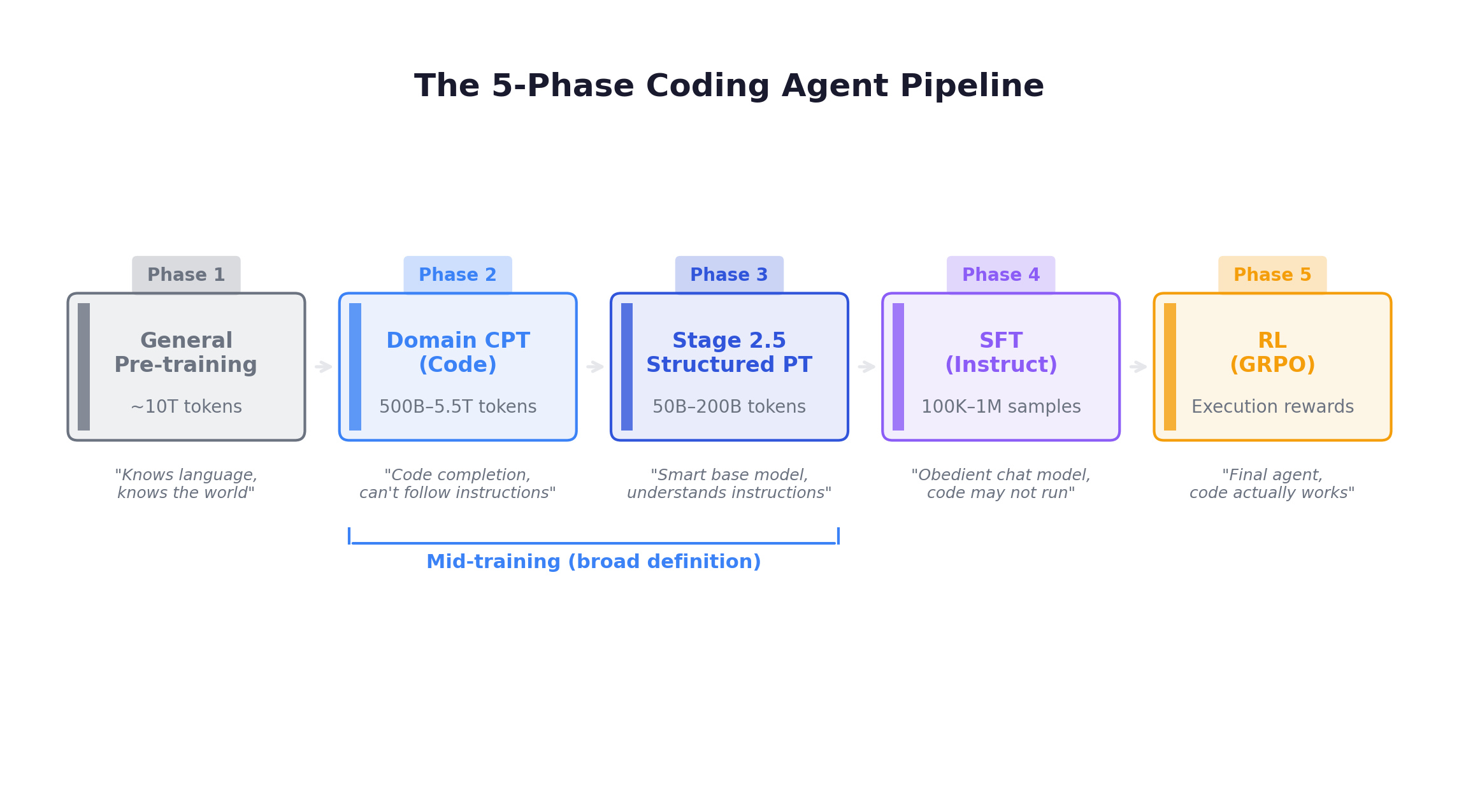

The modern coding agent pipeline, when fully disaggregated, has five phases — not three:

Why does this distinction matter? Because the magic of Stage 2.5 is the scale-format mismatch: it uses structured chat-format data (which teaches instruction-following and edit patterns) but at pre-training token volumes (which prevents overfitting). If you tried to run 100B tokens of CommitPack through the SFT phase, the model would overfit to short Git commit patterns. Placed in Stage 2.5 as part of a diverse high-quality mix, the same data teaches a general-purpose “edit capability” that the SFT phase later activates for complex tasks.

How this post uses the term: Throughout this post, we use “mid-training” in the broad sense — encompassing both Phase 2 (domain CPT) and Phase 3 (Stage 2.5 / structured pre-training). The distinction between the two sub-phases matters for pipeline design (Section 9), but the research findings about mid-training’s role relative to RL (Sections 5-7) apply to both. When we need to distinguish, we’ll specify “code CPT” (Phase 2) or “structured pre-training / Stage 2.5” (Phase 3) explicitly.

If Stage 2.5 Already Uses Chat Format, Why Is SFT Still Necessary?

This raises an interesting question: if Stage 2.5 already trains on chat-formatted instruction data at massive scale, why not skip SFT entirely? From what I can tell, the answer lies in a fundamental distinction: Stage 2.5 teaches capability; SFT teaches alignment.

Although the format boundary between Stage 2.5 and SFT has blurred (both use chat templates), their scale, data distribution, and core objectives remain fundamentally different:

| Dimension | Stage 2.5 (Structured Pre-training) | SFT (Instruction Tuning) |

|---|---|---|

| Token scale | 50B - 200B tokens | 1B - 5B tokens |

| Sample count | 10M - 100M pairs | 100K - 1M pairs |

| Data source | Cleaned natural data (commits, web) + simple synthetic | Carefully constructed complex instructions |

| Epochs | Usually <1 epoch (data is abundant) | 3-5 epochs (data is scarce, must be memorized) |

| Primary goal | Muscle memory (edit skill), domain knowledge | Obedience, safety, tone, persona |

| Long-context | Learning — truly acquiring long-range dependencies | Refinement — maintaining alignment under long input |

Three capabilities that SFT provides and Stage 2.5 cannot:

1. Complex compositional instructions. Stage 2.5 data (commits, StackExchange) involves short, direct tasks — “fix this typo”, “how to iterate a list.” SFT teaches multi-constraint instructions: “Refactor this class to use the factory pattern, change all log levels from Info to Debug, don’t break existing tests, and explain your changes in Chinese.” These compositional constraints barely exist in natural web data and must be explicitly constructed.

2. Safety and refusal. A model that has seen all of GitHub — including malware, attack scripts, and exploits — will happily generate harmful code if asked. SFT includes safety data (red-team examples) that teaches the model to recognize malicious intent and refuse: “I can’t help write an injection script, but I can help you audit for vulnerabilities.”

3. Persona and multi-turn coherence. Commit data is one-shot. StackExchange is single-turn Q&A. SFT trains multi-turn context handling — “No, not that one, I meant the variable on the previous line” — and defines the model’s conversational persona.

I find this analogy helpful: Stage 2.5 is boot camp — massive drilling to build skills and muscle memory. SFT is officer training — learning discipline, judgment, and how to follow complex orders. They seem to serve genuinely different purposes.

For a high-performance coding agent, the SFT budget is typically ~500K carefully curated pairs: ~200K general conversation, ~200K code instructions (Evol-Code), ~50K agent/tool-use trajectories, ~50K safety examples. A rule of thumb from several teams: if the SFT dataset grows beyond ~1M samples, it may be worth moving the excess volume into Stage 2.5 instead.

The Data Funnel: Same Sources, Different Treatment in Phase 2 vs. Phase 3

Something I found subtle but worth highlighting: the same raw data sources (GitHub commits, StackExchange) appear in both Phase 2 (domain CPT) and Phase 3 (Stage 2.5) — but with entirely different filtering criteria, formatting, and training objectives. It’s not “reuse” — it’s a deliberate funnel from broad coverage to precision skill-building.

Commit data across phases:

| Dimension | Phase 2 — “See everything, learn the landscape” | Phase 3 — “Master the skill, learn the format” |

|---|---|---|

| Filtering | Keep top ~50% quality (msg not empty, diff not garbled) | Only commits with clear logic in msg, diffs that include tests, AST-valid code (~1/10 to 1/50 of Phase 2 volume) |

| Format | Raw text / unified diff (see example below) | Chat format + search-and-replace blocks (see example below) |

| Loss | Full-sequence NTP (all tokens count) | Masked — only compute loss on assistant response |

| Purpose | Weak alignment between English and code — model learns “message followed by change” across millions of repos | Train the agent’s ACTION SPACE — model must produce structured edit operations |

Phase 2 format example — raw unified diff, all tokens contribute to loss:

Commit: fix typo

--- a.py

+++ a.py

@@ -1,3 +1,3 @@Phase 3 format example — chat-formatted with SEARCH/REPLACE, loss only on the assistant response:

<|user|>

Fix the typo in the login function

<|assistant|>

<<< SEARCH

def login(user, passwrod):

===

def login(user, password):

>>> REPLACEStackExchange data across phases:

| Dimension | Phase 2 (Domain CPT) | Phase 3 (Stage 2.5) |

|---|---|---|

| Filtering | Keep top ~80% of QA pairs (has an answer, not spam) | Only top ~10% (>10 votes, accepted answer) |

| Format | Flat markdown: Title:\n Body:\n Answer:\n concatenated as text stream | Chat format: <|user|> question <|assistant|> answer |

| Loss | Full-sequence NTP (model reads it like a document) | Masked — loss only on assistant response |

| Purpose | Learn knowledge: API usage, error messages, terminology | Learn Q&A logic: how to explain and reason as an assistant |

Why not skip Phase 2 and use only high-quality data in Phase 3? Two reasons emerge from the literature:

-

Scale prevents overfitting. High-quality commits and StackExchange answers might only total a few billion tokens. Phase 2 needs 500B-5.5T tokens. Using only the premium subset would cause severe overfitting — the model memorizes answers instead of learning to generalize. Lower-quality data provides necessary noise and diversity for robust embeddings.

-

Long-tail knowledge. High-quality data concentrates on popular libraries (PyTorch, React, Django). Cold-corner data — a 2015 Perl CGI script, an obscure Fortran numerical library — has few StackExchange votes and poorly written commit messages. Filtering it out entirely in Phase 2 means the model has essentially zero exposure when encountering legacy code in the wild. Phase 2 teaches breadth; Phase 3 teaches precision.

The practical recipe: Phase 2 keeps the top 50% of commits (by message quality) and 80% of StackExchange QA in raw-text format. Phase 3 takes the top 5-10% of commits reformatted as search-and-replace blocks with loss masking, and the top 10% of StackExchange reformatted as chat with masked loss.

With this clarification in place, every major model family now includes dedicated mid-training phases (sometimes one, sometimes both):

| Model | Phase(s) | Token Budget | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Llama 3.1 | P2 + P3 (annealing) | P3: curated mix | Code ratio boosted to ~50% in annealing phase |

| Qwen 2.5-Coder | P2 (code CPT) | 5.5T tokens | Repository-level training with special tokens |

| DeepSeek-V3 | P2 integrated into pre-training | 14.8T total | 30% code, FIM, multi-token prediction |

| DeepSeek-V3-Base | P2 + P3 | Chat data in pre-training | Stage 2.5 blended into final pre-training stages |

| Code Llama | P2 (code CPT) | 500B tokens | FIM, long-context via RoPE scaling |

| Nemotron | P2 (domain CPT) | 9T tokens | Largest dedicated CPT phase |

| Phi-4 | P3 (structured) | Synthetic-heavy | Pivotal token training, synthetic textbooks |

| OLMo 2 | P2 + P3 | Multiple runs | Model souping (weight averaging across runs) |

| Qwen3-Coder-Next | P2 + P3 | Trillions of tokens | 370 languages, 600B repo-level, chat-FIM |

The Core Technique Toolkit

Mid-training has converged on roughly ten core techniques:

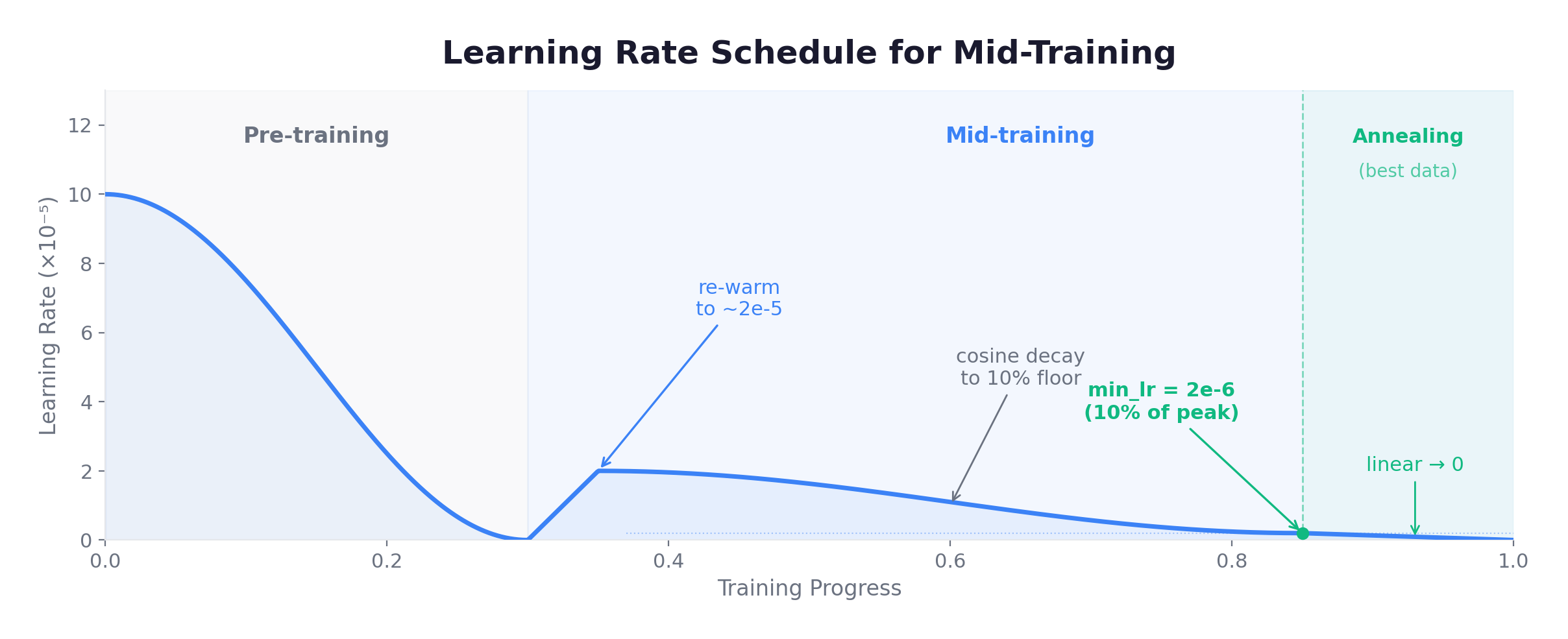

1. Learning Rate Re-Warming. When starting from a pre-trained checkpoint (where LR has decayed to near-zero), re-warming briefly raises the learning rate to 1/3 to 1/10 of the original pre-training peak, then applies cosine decay. Gupta et al., 2023 showed that re-warming + cosine decay with a 1:1 to 4:1 ratio of new-to-replay data works well.

2. Data Replay Buffer. The most dangerous failure mode of mid-training is catastrophic forgetting. The universal countermeasure: mix 5-15% of original pre-training distribution data into every batch. Qwen-Coder uses 10% general text replay alongside 80% code and 10% math — removing the replay buffer causes significant natural language degradation.

3. Fill-in-the-Middle (FIM). For code-focused mid-training, FIM is arguably the single most impactful technique. Instead of always predicting left-to-right, FIM randomly masks a span and trains the model to infill it:

Original: def add(a, b):\n return a + b\n

FIM: <|fim_prefix|>def add(a, b):\n<|fim_suffix|>\n<|fim_middle|> return a + bQwen-Coder applies FIM at a 50% rate using PSM (Prefix-Suffix-Middle) format, with random spans of 10-50% of the file length. This directly teaches code editing — the exact capability needed for SWE-Bench-style tasks.

4. Repository-Level Training. Standard code training treats each file independently. Repository-level training concatenates files from the same repository in dependency order, with special tokens marking boundaries:

<|repo_name|>django/django

<|file_sep|>django/db/models/fields/__init__.py

class Field:

def __init__(self, ...):

...

<|file_sep|>django/db/models/fields/related.py

from django.db.models.fields import Field

class ForeignKey(Field):

...

<|file_sep|>tests/model_fields/test_foreignkey.py

from django.test import TestCase

class ForeignKeyTests(TestCase):

...This teaches cross-file relationships — imports, project structure, test-source connections — that are essential for navigating real codebases.

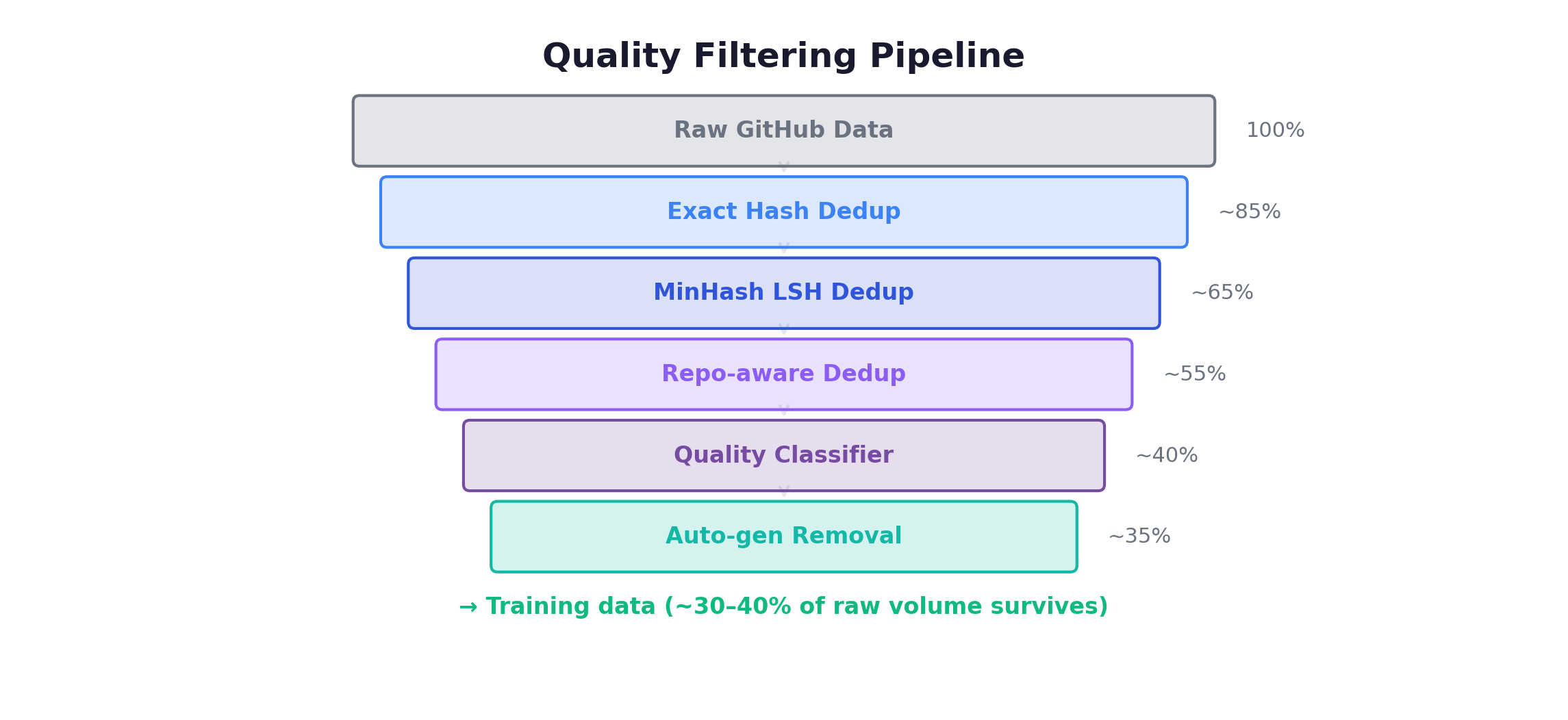

5. Quality Filtering. Model-based quality classifiers score code on signals like docstring presence, linting pass rate, naming convention adherence, and complexity metrics. DCLM showed that 2T filtered tokens can match 10T unfiltered tokens — a 5x efficiency gain from quality alone.

6. Annealing. The final 5-15% of training uses the highest-quality data at a decaying learning rate. Llama 3.1 boosted the code ratio from ~10% to ~50% during annealing, and the math ratio similarly increased. This stage has outsized impact because it is the model’s last exposure before fine-tuning.

7. Synthetic Data Infusion. Phi-4 demonstrated that synthetic data can be more valuable per-token than natural data: 10B synthetic tokens outperformed 1T web tokens for reasoning. Categories include textbook-style explanations, code exercises with test cases, reasoning traces, and agentic trajectories.

8. Long-Context Extension. Increasingly trained during mid-training rather than as a separate phase: gradually increase context length (8K → 32K → 128K → 256K) with curated long-context data.

9. Distillation as CPT. Using outputs from a stronger model (e.g., reasoning traces from DeepSeek-R1) as mid-training data for smaller models. DeepSeek found that distilled reasoning traces are more effective than human-written chain-of-thought.

10. Model Souping. OLMo 2 introduced weight averaging across multiple mid-training runs with different hyperparameters, reducing sensitivity to hyperparameter choices at the cost of extra compute.

The Critical Hyperparameters

| Hyperparameter | Recommended Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Peak learning rate | 1e-5 to 5e-5 | 3-10x lower than pre-training peak |

| Warmup | 1-2% of total steps | Brief re-warming from near-zero |

| Annealing | Final 10-15% of training | Highest quality data, declining LR |

| FIM rate | 50% | Below 30% shows weak editing capability |

| Replay buffer | 5-15% of mix | General pre-training data to prevent forgetting |

| Code ratio | 70-85% | For code-focused mid-training |

| Data repetition | Up to 4 epochs | Beyond 4x, returns diminish rapidly |

From what multiple teams have reported, learning rate is the most sensitive hyperparameter — too high and the model forgets; too low and it doesn’t adapt.

2. Knowledge vs. Strategy — Why Mid-Training Is the Ceiling

The Core Thesis

Here’s a conceptual model I find useful for thinking about what each training stage contributes:

| Stage | Learns To… | Capabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | ”Know words” | General language understanding, world knowledge |

| Mid-training | ”Know code” | Domain knowledge, tool formats, code structure, debugging |

| SFT | ”Know the format” | Output formatting, instruction following, conversation |

| RL | ”Know strategy” | When to search vs. edit, how to decompose, error recovery |

This leads to what I think is the key implication: mid-training determines the ceiling of what RL can achieve. RL can optimize strategy — the sequence of actions an agent takes — but it cannot manufacture knowledge the model doesn’t have. If the model doesn’t understand Python’s import system, no amount of RL will teach it to navigate cross-module dependencies.

Evidence: DeepSeek-R1-Zero

The most vivid demonstration comes from DeepSeek’s R1-Zero experiment — applying GRPO directly to the base model with no SFT or mid-training. Reasoning emerged spontaneously:

| Training Step | Emergent Behavior |

|---|---|

| ~100 | Longer responses (model discovers more tokens = more exploration) |

| ~500 | First structured reasoning attempts |

| ~1,000 | ”Aha moment” — spontaneous chain-of-thought appears |

| ~5,000 | Consistent multi-step reasoning |

| ~10,000 | Self-verification emerges (“Let me check…“) |

This proves RL can induce reasoning from a knowledge-rich base. But R1-Zero also had critical failures: unstructured text, mixed languages mid-response, inconsistent formatting. The full R1 model — with cold-start SFT and better post-training — massively outperformed it.

What I take away from this: RL can discover strategy, but the knowledge base must already be in place. R1-Zero worked because DeepSeek-V3 was pre-trained on 14.8T tokens including 30% code. For a model without code-heavy pre-training or mid-training, RL on coding tasks would simply fail.

The Full DeepSeek-R1 Pipeline

The R1-Zero experiment was instructive, but the production R1 pipeline tells the full story. It has five stages, and the interplay between them illustrates the knowledge-strategy separation precisely:

| Stage | Name | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Pre-training (14.8T tokens) | 30% code, 55% text, 10% math, 5% other; FIM at 0.5; MoE: 671B total, 37B active; multi-token prediction |

| 1 | Cold-Start SFT | ~thousands of long CoT examples; teaches the FORMAT of reasoning, not reasoning itself; quality over quantity |

| 2 | Reasoning RL via GRPO | G=64 completions per prompt, no critic network; rewards: correctness (math/code) + format compliance; this is where reasoning EMERGES |

| 3 | Rejection Sampling + SFT (~800K) | 600K reasoning + 200K general; uses Stage 2’s model to generate, filters for quality; consolidates reasoning with general skills |

| 4 | RL Alignment | Final alignment pass for helpfulness + safety |

The GRPO algorithm itself was partly designed around infrastructure constraints — eliminating the critic network removes 84 GB of memory for a 7B model, making RL feasible on fewer GPUs:

def compute_grpo_advantages(rewards, group_size=64):

"""For each prompt, sample G completions and

normalize rewards within the group.

No critic network needed."""

# rewards: [batch_size, group_size]

mean = rewards.mean(dim=1, keepdim=True)

std = rewards.std(dim=1, keepdim=True) + 1e-8

advantages = (rewards - mean) / std

return advantagesNotice the division of labor: Stages 0-1 install knowledge and format (mid-training territory). Stages 2-4 discover and optimize strategy (RL territory). The cold-start SFT in Stage 1 is the bridge — it gives RL a starting format to work with, but the actual reasoning capability comes from RL exploration.

For code-specific rewards in SWE-Bench-style tasks, the reward function provides graded signal:

def swe_bench_reward(patch, test_suite, original_state):

"""Graduated reward for SWE-Bench-style code fixing."""

if not patch.is_valid_diff():

return 0.0 # Syntactically invalid patch

applied = apply_patch(original_state, patch)

if applied is None:

return 0.05 # Well-formatted but doesn't apply

results = run_tests(applied, test_suite)

if results.all_pass:

return 1.0 # Perfect fix

elif results.previously_failing_now_pass:

if results.has_regressions:

return 0.5 # Fixed target bug but broke something

return 0.8 # Fixed target bug, some tests still fail

return 0.1 # Applied but didn't fix the issueThe Cold-Start Problem

For agentic RL, the cold-start problem is severe. Consider training a coding agent with GRPO on SWE-Bench tasks (binary reward: did the patch fix the failing tests?):

| Without Mid-Training (Cold Start) | With Code Mid-Training | |

|---|---|---|

| Tool calls | Invalid → reward = 0 | Valid (learned format during mid-training) |

| File navigation | Wrong files → reward = 0 | Plausible files (learned repo structure) |

| Patches | Syntactically invalid → reward = 0 | Syntactically valid (learned code patterns) |

| Result | Reward almost always 0. RL has nothing to learn from. | Some patches work, some don’t. RL has meaningful signal to optimize. |

The agentic RL frameworks (AgentRL, Agent-R1, Planner-R1) all require a mid-trained or SFT’d starting model. GRPO has a hidden requirement: the group of G completions must contain some correct answers. If all 64 completions receive reward 0, the advantage is uniformly zero and no learning occurs.

Planner-R1’s finding is particularly instructive: an 8B model with dense reward shaping achieves 56.9% on TravelPlanner — competitive with 32B models — but even with shaped rewards, the 8B model still needs to understand what the tools are and how to call them. That understanding comes from mid-training.

Quantifying the Gap

3. The Qwen-Coder Blueprint

If mid-training determines the RL ceiling, the concrete question becomes: what should a mid-training run look like? The most thoroughly documented answer comes from Qwen-2.5-Coder.

The Pipeline

Qwen-2.5-Coder continues training from Qwen-2.5 (18T general tokens) with 5.5T additional code-heavy tokens across 92 languages:

| Stage | Phase | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Start | Qwen-2.5 Base | 18T tokens, general |

| 1 | Code CPT | Bulk of 5.5T tokens; 80% code, 10% math, 10% general replay; repo-level training with special tokens; FIM at 50% rate |

| 2 | Long-Context Extension | 8K → 128K |

| 3 | Annealing | Highest quality data, declining LR |

| Output | Qwen-2.5-Coder Base | Ready for SFT and RL |

Repository-Level Training

This is Qwen-Coder’s most influential contribution. Files from the same repo are concatenated in dependency order with <|repo_name|> and <|file_sep|> special tokens. The model learns import chains, project structure, test-source correspondence, and API usage patterns across files.

This is critical for SWE-Bench tasks — and based on Qwen’s experiments, it can’t realistically be taught in SFT or RL — the model needs to internalize repository structure during mid-training, from seeing millions of repositories.

What does the model learn from repository-level training that it can’t learn from file-level training?

| File-Level Training Teaches | Repository-Level Training Adds |

|---|---|

| Syntax and semantics | Import resolution across files |

| Function/class patterns | Where tests live relative to source |

| Local variable usage | Configuration files and their effects |

| Single-file algorithms | Database models → views → templates flow |

| API definitions → client usage patterns | |

Package structure and __init__.py chains |

The practical difference: a file-level trained model might generate a correct function in isolation. A repo-level trained model knows that from django.db.models import Field means there’s a Field class somewhere in django/db/models/, knows roughly what methods it has, and knows that changing it requires updating tests in tests/model_fields/. This contextual awareness is what SWE-Bench demands.

Language Distribution

The 92 programming languages in Qwen-Coder are not equally represented:

| Language | Share | Language | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| Python | 25% | Go | 4% |

| JavaScript | 8% | Rust | 3% |

| TypeScript | 7% | Shell | 3% |

| Java | 7% | PHP | 3% |

| C/C++ | 8% | Ruby | 2% |

| C# | 4% | 70+ others | 17% |

Python dominates because (a) it’s the most common language on GitHub, (b) SWE-Bench is Python-only, and (c) Python reasoning transfers well to other languages. The long tail of 70+ languages ensures the model has at least some exposure to diverse syntax patterns.

FIM Details

PSM format at 50% rate, with random spans of 10-50% of file length:

def apply_fim(code: str, fim_rate: float = 0.5) -> str:

if random.random() > fim_rate:

return code # 50% standard left-to-right

span_ratio = random.uniform(0.1, 0.5)

span_length = int(len(code) * span_ratio)

start = random.randint(0, len(code) - span_length)

prefix = code[:start]

middle = code[start:start + span_length] # Model must predict this

suffix = code[start + span_length:]

return f"<|fim_prefix|>{prefix}<|fim_suffix|>{suffix}<|fim_middle|>{middle}"Below 30%, the model shows weak editing capability. Above 70%, left-to-right generation quality degrades. The 50% sweet spot was independently validated across Qwen-Coder and Code Llama.

Quality Filtering Pipeline

The Results

| Benchmark | Before Mid-Training | After Mid-Training | Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| HumanEval | 57.3% | 88.4% | +31.1% |

| MBPP | 66.2% | 83.5% | +17.3% |

| MultiPL-E | 42.1% | 70.6% | +28.5% |

These are massive gains from next-token prediction on well-curated code alone — no RL, no reward engineering, no environment setup.

Key Lessons (from the Qwen-Coder reports)

- Start from a strong general base. Code mid-training on a weak base model doesn’t work.

- Quality > quantity, with a quantity floor. Filtering matters more than token count, but you still need hundreds of billions of tokens.

- Repository-level context can’t be taught post-hoc. It requires exposure to millions of repos during mid-training.

- The 10% replay buffer matters a lot. Removing it causes measurable NL degradation in Qwen’s experiments.

- Annealing has outsized impact. The last 10-15% of training disproportionately affects downstream performance.

Qwen-2.5-Coder established the blueprint for code mid-training as of late 2024 — repo-level training, FIM at 50%, quality filtering, replay buffers. But the blueprint assumed you have the data. For agentic mid-training, the data problem is acute: multi-turn tool-use trajectories barely exist in the wild. Section 4 examines how to manufacture them. After that, several deeper questions remained open: How should mid-training interact with RL? How much compute belongs in each stage? Can RL signals flow backward to improve mid-training itself? Sections 5-7 examine the research that answered these questions, and in Section 8, we’ll see how Qwen3-Coder-Next incorporated all of these advances — scaling from 92 to 370 languages, adding multi-scaffold agentic trajectories, and achieving results that would have seemed implausible a year earlier.

4. Data Synthesis at Scale

In practice, the biggest bottleneck for agentic mid-training seems to be data, not compute. Agentic trajectories (multi-turn tool-use sequences, debugging sessions, repository-level edits) are rare in the wild. GitHub has plenty of code, but very few examples of an agent systematically debugging a failing test, localizing a bug, and applying a fix.

SWE-smith: The Environment-First Approach

SWE-smith (Yang et al., 2025) is the most important advance in training data synthesis for coding agents. The key insight: build the execution environment first, then synthesize bugs within it.

SWE-Bench’s conventional approach creates a Docker environment per task instance (~50-150 TB for the full dataset, hundreds of human hours). SWE-smith inverts this: one Docker image per repository, then synthesize bugs programmatically:

| Step | Action | Output |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Take top PyPI packages (5,000+ stars) | Candidate repositories |

| 2 | Run SWE-agent to install + verify tests | ~7 min human review per repo |

| 3 | ONE Docker image per repo | 295 GB total |

| 4 | Synthesize bugs via 4 strategies | 50,137 instances from 128 repos |

Cost: ~20 hours human labor, $1,360 compute

Four Bug Synthesis Strategies

LM Modify (56% yield, $0.004/candidate) — Prompt an LM to introduce subtle logical bugs. Cheapest, highest yield.

LM Rewrite (35% yield, $0.04/candidate) — Give LM only function header + docstring, ask for re-implementation. Bugs emerge naturally from imperfect reimplementation — more realistic than intentional insertion.

Procedural Modification (40.2% yield, zero cost) — 13 AST-level transformations:

TRANSFORMATIONS = [

"remove_conditional", "change_operator",

"invert_boolean", "shuffle_lines",

"remove_return", "change_constant",

"remove_exception_handler", "swap_arguments",

"remove_loop_break", # ... 13 total

]PR Mirror (33.8% yield, $0.06/candidate) — Collect real PRs, use LM to revert changes. Most realistic, most expensive.

Every candidate goes through automated validation: apply patch → run test suite → keep only if ≥1 previously-passing test now fails.

Scaling Results

SWE-smith data with rejection sampling fine-tuning (no RL) achieves:

| Training Data | SWE-Bench Verified |

|---|---|

| 100 trajectories | 14.3% |

| 400 trajectories | 27.8% |

| 1,600 trajectories | 33.4% |

| 5,016 trajectories | 40.2% |

Log-linear scaling, not saturating. And a key finding: repository diversity > task difficulty. Performance scales logarithmically with number of training repos, but task difficulty shows no correlation with downstream effectiveness.

Beyond SWE-smith: Agentic Trajectory Generation

For mid-training at the billion-token scale, you need more than static bug-fix pairs. You need full agentic trajectories — multi-turn sequences showing how an agent explores, reasons, and fixes issues. The pipeline:

def generate_agentic_trajectory(task, model, environment, max_turns=30):

"""Generate a multi-turn agentic trajectory for a coding task."""

trajectory = []

state = environment.reset(task)

for turn in range(max_turns):

# Agent thinks and decides action

action = model.generate(

system_prompt=AGENT_SYSTEM_PROMPT,

context=state.to_string(),

tools=["search_files", "read_file", "edit_file",

"run_tests", "bash_command"]

)

# Execute in sandboxed environment

observation = environment.step(action)

trajectory.append({

"turn": turn,

"thought": action.thought, # Agent's reasoning

"action": action.tool_call, # Tool invocation

"observation": observation # Environment response

})

if observation.is_terminal:

break

# Evaluate: did the trajectory solve the task?

reward = environment.evaluate(task, state)

return trajectory, reward

# Scale: generate across thousands of tasks

# Filter: keep only successful (or partially successful) trajectories

# Format: convert to training-ready sequences with proper maskingDifferent agent frameworks produce different trajectory formats (ReAct, function-calling, code execution), and including all of them during mid-training prevents the model from overfitting to a single scaffolding style. This is a key lesson from Qwen3-Coder-Next (Section 8).

Additional synthesis approaches that complement SWE-smith:

Commit-based data mining: GitHub commits provide natural (buggy_version, fixed_version) pairs. Extract diff + pre-commit state + commit message; verify that the fix resolves test failures. This produces issue-to-patch training data at massive scale.

Sub-skill decomposition: Following Agent-FLAN’s finding, train on decomposed sub-skills (tool use, planning, reflection, multi-turn interaction) separately before combining into full trajectories. This is more effective than training on end-to-end trajectories alone.

Negative examples: Generate incorrect tool calls and failed plans alongside correct ones. Agent-FLAN found that a 4:1 positive-to-negative ratio significantly improves robustness, teaching the model what not to do.

Data Mixing for Agentic Mid-Training

Combining all data sources, the recommended mix:

| Data Source | Ratio | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Code (file-level, quality-filtered) | 25% | Core code understanding |

| Code (repo-level, dependency-ordered) | 15% | Cross-file relationships |

| Issue-to-patch pairs | 10% | Bug understanding and fixing |

| Agentic trajectories (tool-use) | 10% | Tool-use patterns |

| Reasoning traces (CoT) | 10% | Step-by-step reasoning |

| Debugging traces | 8% | Error analysis skills |

| TDD data (failing test → fix) | 5% | Test-driven development |

| Code navigation / search data | 5% | Codebase exploration |

| General text replay | 12% | Anti-forgetting |

With the data problem addressed, we can turn to the deeper question: how should mid-training and RL interact? The next three sections present controlled studies that reshape the conventional “mid-train first, RL later” pipeline.

5. Front-Loading Reasoning

The traditional view treats reasoning as a post-training concern. Two NVIDIA papers challenge this fundamentally.

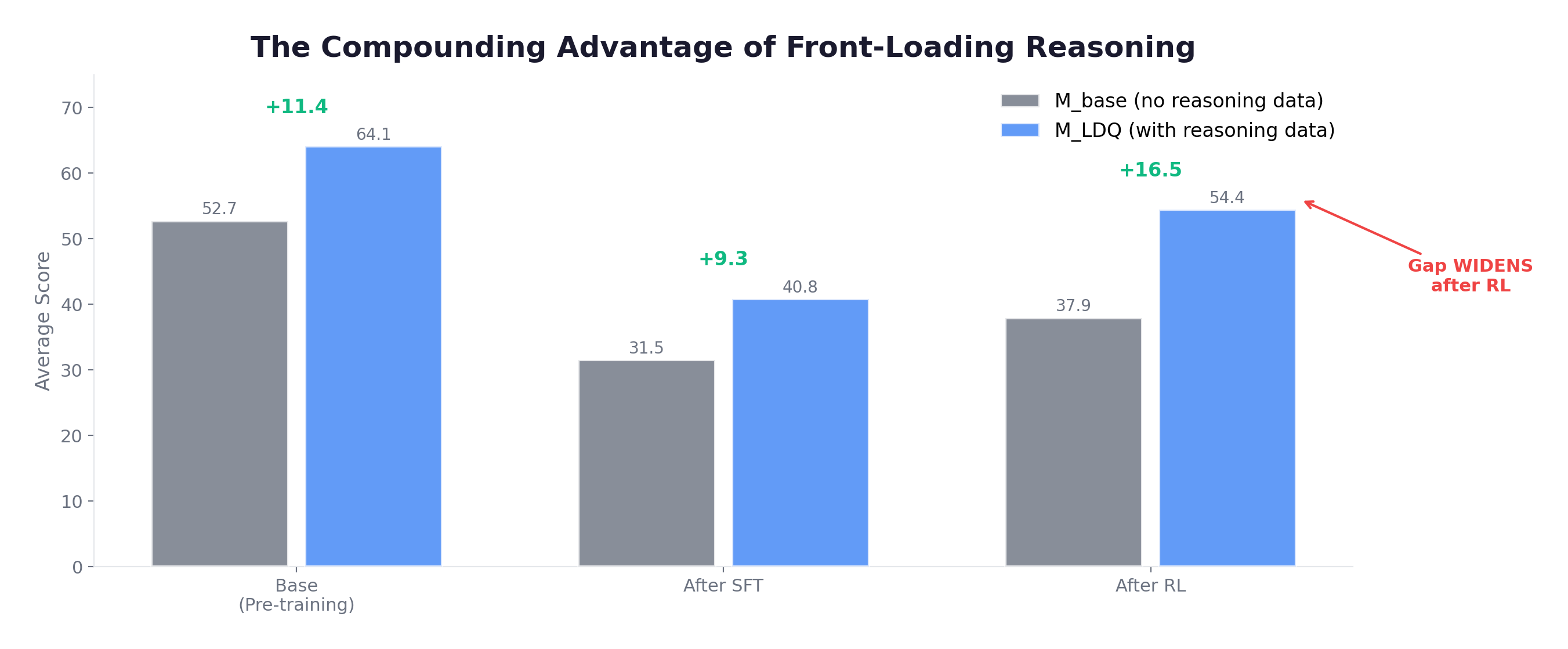

Front-Loading Reasoning (Akter et al., 2025)

This paper asks: what happens if we include reasoning data during pre-training instead of deferring it to SFT?

The authors train 8B models from scratch on 1T tokens with four pre-training data configurations (with and without reasoning data), then systematically apply SFT and RL.

Finding 1: The Compounding Advantage.

On AIME: 12.29% (base+RL) vs. 45.21% (reasoning+RL) — a 33% absolute gap. This refutes the “catch-up” hypothesis: no amount of post-training compensates for a weak pre-training data mix.

Finding 2: The Asymmetric Principle.

| Diversity-First | Quality-First | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | 64.09 avg (winner) | 54.98 avg |

| SFT | 31.54 avg | 44.99 avg (winner) |

In other words, different stages seem to have different optimal data strategies. Mid-training benefits from casting a wide net (diverse reasoning data); SFT benefits from being ruthlessly selective (highest-quality chain-of-thought).

Finding 3: Latent Effects. High-quality pre-training data has benefits invisible at the pre-training checkpoint that manifest after SFT — a +4.25% advantage that appeared only post-alignment. This means evaluating mid-training checkpoints in isolation underestimates the value of high-quality data.

Finding 4: Naive SFT Scaling Hurts. Doubling SFT data volume with mixed-quality examples actually decreases math performance by 4.92%. The heavy lifting of data volume should happen during mid-training, not SFT.

RLP: RL as a Pretraining Objective (NVIDIA, ICLR 2026)

RLP goes further: RL can be the pre-training objective itself. It defines a universal reward signal based on information gain:

For any document d = [t₁, t₂, ..., tₙ]:

1. Generate a reasoning chain r for context c = [t₁, ..., tₖ]

2. Compute: reward = log P(tₖ₊₁ | c, r) - log P(tₖ₊₁ | c)

= "How much does reasoning help predict the next token?"No verifier needed — the document itself provides supervision. Properties:

- Verifier-free: Works on any document stream

- Dense signal: Every token provides reward

- Extraordinarily data-efficient: 0.125% of data → 35% accuracy improvement on 12B model

Results on Nemotron-Nano-12B: 42.81% → 61.32% average (+18.51%) with just 0.125% of training data processed through RLP.

A Practical Training Schedule

Combining both papers, the authors recommend a three-phase approach to mid-training:

| Phase | Compute | Objective | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80% | Standard NTP | Build knowledge base with diverse reasoning data mixed in (Front-Loading: code + math + science reasoning) |

| 2 | 15% | NTP + RLP interleaved | Install reasoning via RL-in-pretraining; dense reward from information gain; extraordinarily data-efficient |

| 3 | 5% | High-quality annealing | Consolidate with best data at declining LR; plant “latent seeds” that manifest during SFT/RL |

The picture that emerges: reasoning is not something you bolt on at the end — it’s a foundational capacity that benefits from being present in the training data from early stages.

Implications

- These results make a strong case that reasoning data belongs in mid-training, not just SFT/RL — the compounding advantage means every reasoning token in mid-training is worth more than the same token in SFT.

- RL-like objectives can be embedded directly in mid-training (via RLP).

- The clean separation between “pre-training for knowledge” and “post-training for reasoning” no longer holds.

6. The Interplay — Controlled Evidence

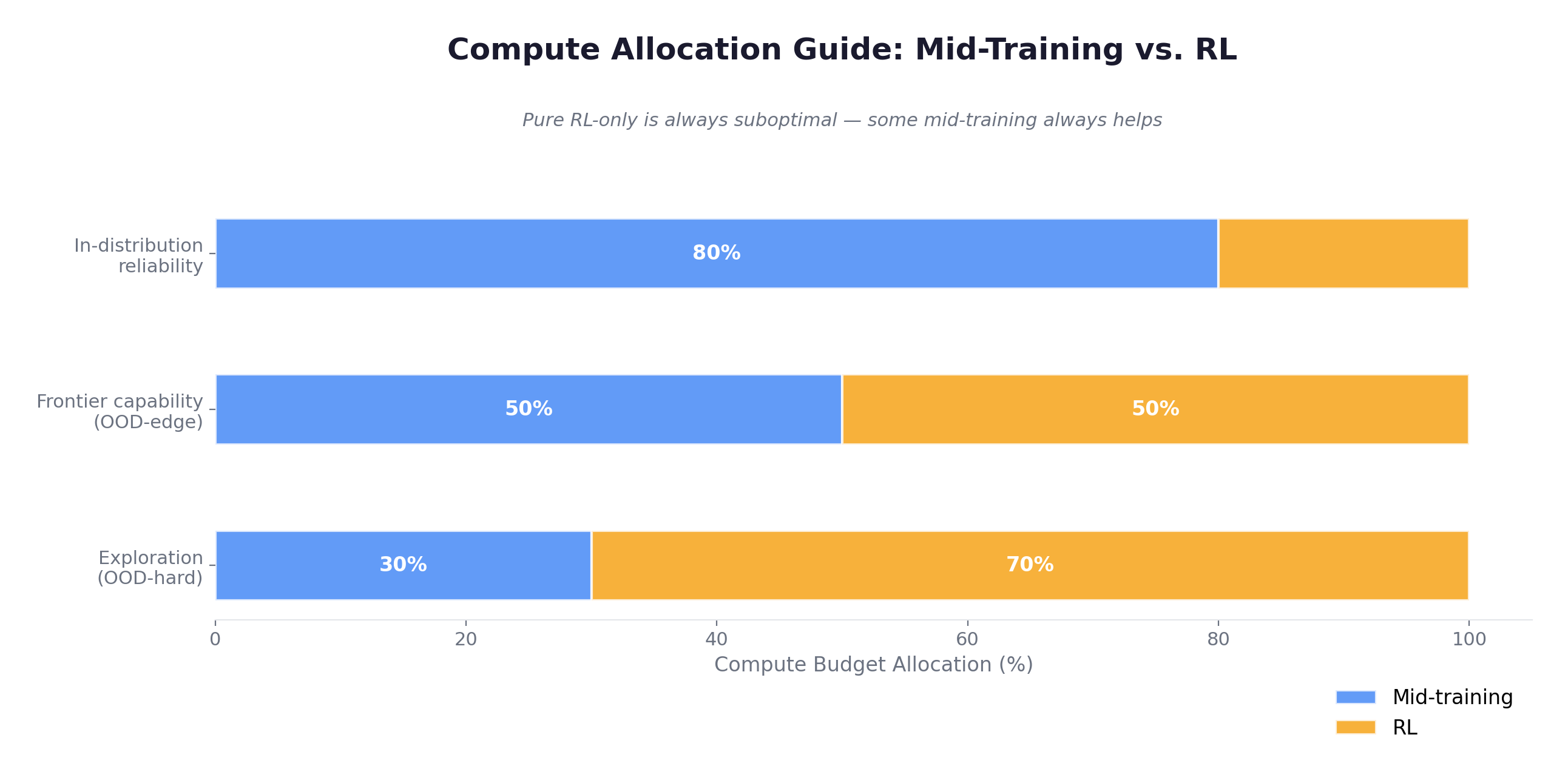

While NVIDIA’s work shows that reasoning should be front-loaded, Zhang, Neubig, and Yue (CMU, 2025) answer the harder question: how much compute should go to mid-training vs. RL?

The Experimental Framework

The authors use synthetic reasoning tasks (DAGs of arithmetic operations) with fully controllable difficulty:

Example (op=4, "easy"): Example (op=12, "hard"):

x₁ = 15 x₁ = 7

x₂ = x₁ + 3 = 18 x₂ = x₁ + 5 = 12

x₃ = x₂ × 2 = 36 ...

x₄ = x₃ - x₂ = 18 x₁₂ = f(x₁₁, x₉) = ???They define three regimes:

- In-distribution: op = 2-10 (seen during training)

- Edge of competence: op = 11-14 (just beyond training)

- Out of distribution: op = 17-20 (far beyond training)

Finding 1: RL Only Works at the Edge of Competence

| Difficulty Regime | pass@1 | pass@128 | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-distribution (op=2-10) | Improves | Unchanged | RL sharpens but doesn’t extend |

| Edge of competence (op=11-14) | — | +42% | RL genuinely extends capability |

| Too hard (op=17-20) | No change | No change | RL cannot learn what it cannot solve |

RL can only improve tasks where the model has partial success. Mid-training’s job is to push the “edge of competence” outward — giving the model enough knowledge that RL can sharpen.

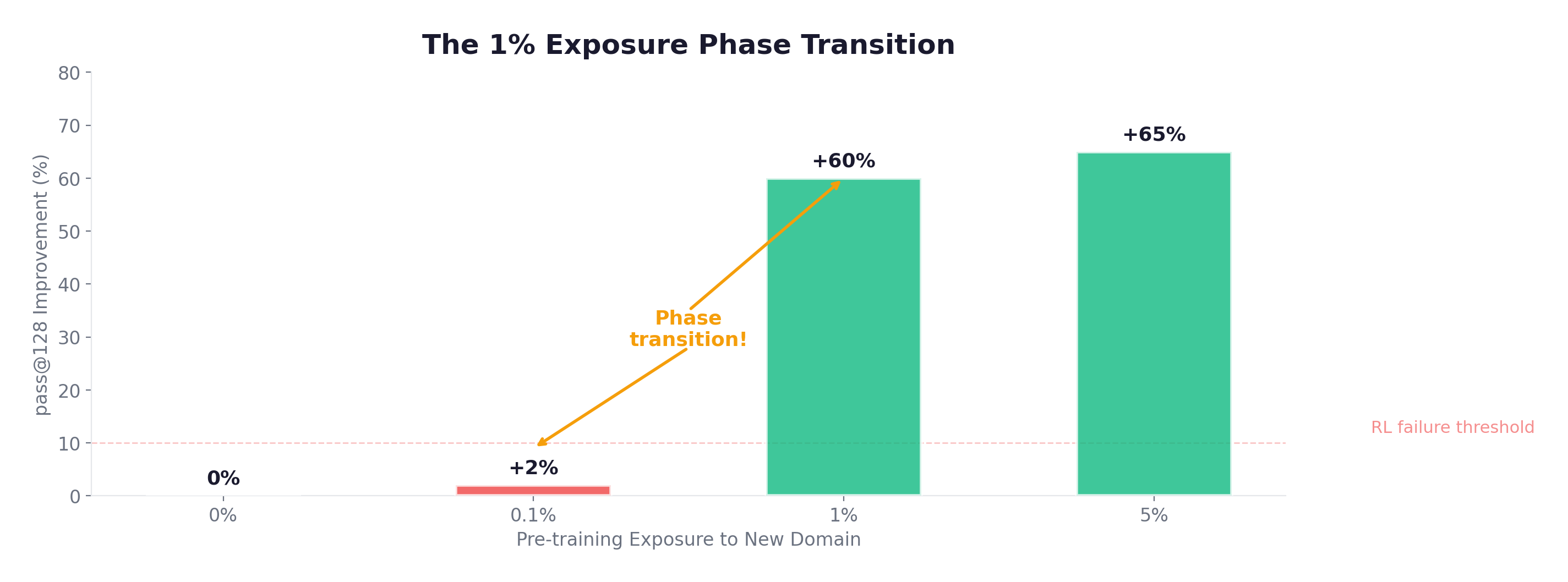

Finding 2: The 1% Exposure Phase Transition

A phase transition, not a gradual curve. Even 1% Rust in the mid-training mix (vs. 0%) can be the difference between RL succeeding or completely failing on Rust tasks.

Finding 3: Mid-Training Outperforms RL-Only

Under normalized compute budgets:

| Compute Allocation | OOD-hard Performance |

|---|---|

| RL-only (100% RL budget) | Baseline |

| Mid-training + heavy RL (50/50) | +10.8% over RL-only |

| Mid-training + light RL (80/20) | Best pass@1 on OOD-edge |

The optimal allocation depends on the goal:

Finding 4: Process Rewards Prevent Hacking

Composite reward (0.2 outcome + 0.8 process) yields +4-5% pass@1 on OOD tasks. More importantly, outcome-only models learn shortcuts via wrong reasoning; process rewards enforce correct intermediate steps.

For agentic SWE tasks: intermediate rewards (correct localization, patch compiles, right files addressed) are more valuable than pure outcome rewards (all tests pass).

Finding 5: Topological Novelty

A fascinating side result: on harder tasks (op=15-20), models with sufficient pre-training exposure generate genuinely novel reasoning structures — DAG topologies not seen during training. This is evidence that RL can discover new reasoning strategies, not just replay memorized ones. But it only occurs when the base model has enough knowledge to attempt the task.

For agentic coding, this suggests that RL can discover novel debugging strategies (e.g., new patterns of search → read → hypothesize → test) if the base model has sufficient code understanding from mid-training. Without that foundation, the model generates random action sequences rather than exploring novel-but-structured approaches.

Connecting to Practice

Here’s how I see the Interplay paper’s findings translating to agentic coding models:

-

Edge-of-competence RL curricula. Starting with easier SWE tasks where the agent sometimes succeeds, then gradually increasing difficulty, appears to be the most compute-efficient approach — tasks that are too easy or too hard contribute little learning signal.

-

Even 1% domain exposure matters. Extending to new languages or frameworks? Including a small amount of relevant data in mid-training seems sufficient to unlock RL generalization — the cost is minimal but the impact is binary.

-

Split compute between stages. Under any fixed budget, the data suggests that splitting between mid-training and RL beats RL-only. The question is the ratio, not whether to split.

-

Process rewards help for multi-step tasks. Multi-step agentic tasks appear to benefit disproportionately from intermediate reward signals, consistent with broader findings in RL for sequential decision-making.

7. ReMiT — The Feedback Loop

Everything discussed so far follows the unidirectional pipeline: mid-training produces a better base → RL exploits it. ReMiT (Huang et al., 2026) breaks this directionality, creating a self-reinforcing flywheel.

The Core Insight

Standard next-token prediction treats all tokens equally. But not all tokens matter equally for reasoning. Words like “Therefore”, “However”, and code control flow keywords are disproportionately important. An RL-trained model already knows which tokens matter — its probability distribution is shifted toward these “pivotal” tokens.

ReMiT uses this shift to reweight the mid-training loss.

The Algorithm

Step 1: Compute the token-level log-probability gap:

Step 2: Center per sequence to normalize difficulty:

Step 3: Map to weights via scaled sigmoid with clipping:

Step 4: Apply weighted NTP loss:

The implementation:

import torch

import torch.nn.functional as F

class ReMiTWeighter:

def __init__(self, epsilon: float = 0.2):

self.epsilon = epsilon

@torch.no_grad()

def compute_weights(self, base_logits, rl_logits, labels):

# Step 1: Log-probability gap

base_lp = F.log_softmax(base_logits, dim=-1)

rl_lp = F.log_softmax(rl_logits, dim=-1)

base_lp = base_lp.gather(-1, labels.unsqueeze(-1)).squeeze(-1)

rl_lp = rl_lp.gather(-1, labels.unsqueeze(-1)).squeeze(-1)

delta = rl_lp - base_lp

# Step 2: Sequence-level centering

mask = (labels != -100).float()

seq_mean = (delta * mask).sum(-1, keepdim=True) / mask.sum(-1, keepdim=True)

delta_centered = delta - seq_mean

# Step 3: Scaled sigmoid with clipping

weights = 2.0 * torch.sigmoid(delta_centered)

weights = weights.clamp(1.0 - self.epsilon, 1.0 + self.epsilon)

return weights # [batch, seq_len], range [0.8, 1.2]What Tokens Get Upweighted?

| Token Category | Avg Weight | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Discourse connectives | 1.15–1.20 | ”Therefore”, “However”, “Thus” |

| Logical verbs | 1.12–1.18 | ”implies”, “requires”, “depends” |

| Code control flow | 1.10–1.15 | if, else, return, break |

| Mathematical operators | 1.08–1.12 | +, *, =, comparisons |

| Structural markers | 1.05–1.10 | Indentation, brackets, newlines |

| Content words | 0.95–1.05 | Variable names, string literals |

| Filler tokens | 0.80–0.90 | Articles, prepositions |

Results

Across three model families:

| Model | Vanilla NTP | ReMiT | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| OLMo-1B | 22.35 | 27.56 | +5.21 |

| SmolLM3-3B | 36.80 | 38.58 | +1.78 |

| Youtu-LLM-2B | 32.61 | 36.93 | +4.32 |

Convergence: ReMiT reaches baseline performance in 6x fewer training steps. Throughput drops 43% per step (extra forward pass through RL reference), but total GPU hours drop 3.5x.

Post-training transfer: The advantage persists through SFT → DPO → RL (+2% sustained).

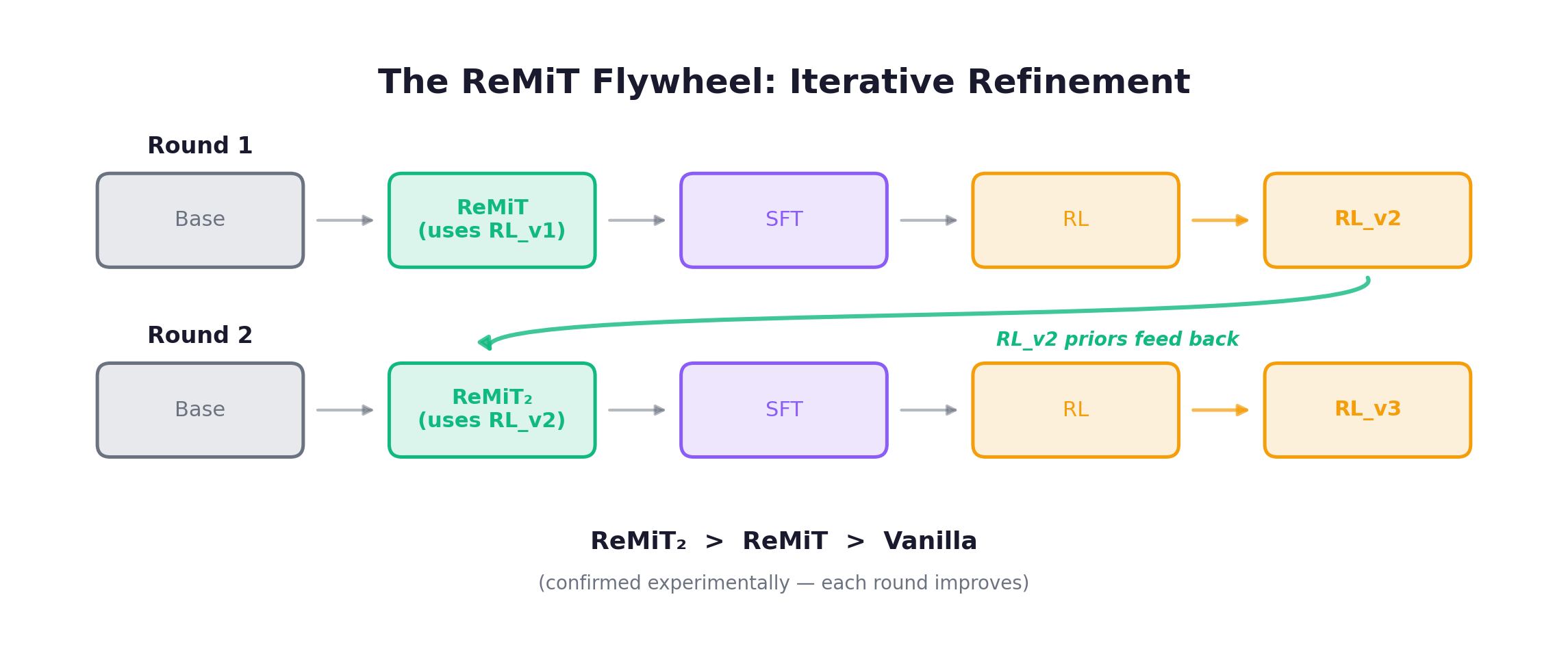

The Flywheel

Each round produces a better RL model → better reference for mid-training → even better RL model.

ReMiT vs. Knowledge Distillation

KD looks better during mid-training but its advantage disappears after post-training. Why? KD creates extremely low KL divergence to the RL model, destroying distributional diversity needed for continued training. ReMiT’s conservative weight range (0.8 to 1.2) preserves diversity while prioritizing important tokens — nudging the distribution rather than forcing it.

The Bigger Picture

The linear pipeline becomes a loop. Combined with RLP (RL-as-pretraining from Section 5), the stages are no longer sequential — they’re interleaved and mutually reinforcing. This is the “with” in “mid-training with agentic RL.”

8. Case Study — Qwen3-Coder-Next

In Section 3, we examined the Qwen-2.5-Coder blueprint: 5.5T tokens, 92 languages, repo-level training with FIM. That was the state of the art in late 2024. Qwen3-Coder-Next, released in early 2026, represents a generational leap — not just in scale (trillions of tokens, 370 languages) but in incorporating the very research advances we’ve covered in Sections 4-7: large-scale agentic trajectory synthesis, multi-scaffold diversity, and best-fit packing that preserves document boundaries. It’s perhaps the best public example of what all these techniques look like when they come together. But first, some context on how rapidly the field has moved.

The SWE-Bench Trajectory

SWE-Bench Verified — a curated subset of real GitHub issues with reproducible test environments — has become the de facto benchmark for agentic coding capability. The performance trajectory tells a story of compounding infrastructure, data, and algorithmic improvements:

| Period | System | SWE-Bench Verified |

|---|---|---|

| Apr 2024 | SWE-agent + GPT-4 | ~18% |

| Jun 2024 | Agentless | ~27% |

| Mid 2024 | Claude 3.5 Sonnet + SWE-agent | ~33% |

| Late 2024 | Amazon Q / OpenHands + Claude | ~35-41% |

| Early 2025 | Frontier systems | ~49-53% |

| Mid 2025 | SWE-agent-LM-32B (open-source, SWE-smith) | 40.2% |

| Late 2025 | Various | ~55-65% |

| Jan 2026 | Claude Opus 4.5 + Live-SWE-agent | 79.2% |

| Jan 2026 | Gemini 3 Pro | 77.4% |

| Jan 2026 | Qwen3-Coder-Next (3B active!) | 74.2% |

From ~18% to ~79% in under two years. SWE-Bench Pro (a harder variant) tells a different story: even the best system (Qwen3-Coder-Next) tops at 44.3%, and GPT-5 manages only 23.3%. Real-world software engineering remains far from solved.

What stands out to me from this trajectory: the improvements come from three mutually reinforcing factors — better base models (improved through mid-training), better agent scaffolding (tool design, retrieval, multi-agent coordination), and RL refinement. Mid-training is the foundational layer.

The Model

- 80B total parameters, 3B active per token (MoE)

- Hybrid architecture: Gated Attention + Gated DeltaNet (linear attention for efficient long-context)

- 262K context length

- Multi-scaffold: Trained across SWE-Agent, Mini-SWE-Agent, OpenHands, Claude-Code scaffolds

| Benchmark | Qwen3-Coder-Next (3B active) | Claude Opus 4.5 (full) | DeepSeek-V3.2 (37B active) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWE-Bench Verified | 71.3% | 79.0% | 72.6% |

| SWE-Bench Pro | 44.3% | 40.8% | 40.9% |

| SWE-Bench Multilingual | 62.8% | ~65% | ~58% |

A 3B-active model matching or exceeding a 37B-active model. The training pipeline, not architecture alone, drives this.

Mid-Training: The Main Event

The mid-training phase processes trillions of tokens with several innovations:

Massively expanded natural data: Scaling from Qwen-2.5-Coder’s 92 languages to 370, with ~600B tokens of repo-level data and 262K context — a 4x expansion in language coverage and substantially longer context.

Text-Code Grounding — a new data type: web documents from Common Crawl rewritten by Qwen3-Coder-480B (teacher) to include better code examples and clearer explanations:

| Benchmark | Original Web Text | Reformatted by 480B | Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| EvalPlus | 54.38 | 63.09 | +8.71 |

| MultiPL-E | 36.02 | 48.35 | +12.33 |

Simply having a stronger model rewrite web documents about programming produces substantially better training data.

Multi-scaffold agentic trajectories: Generated using SWE-Agent, Mini-SWE-Agent, OpenHands, Claude-Code, Qwen-Code, and Terminus with Qwen3-Coder-480B as teacher.

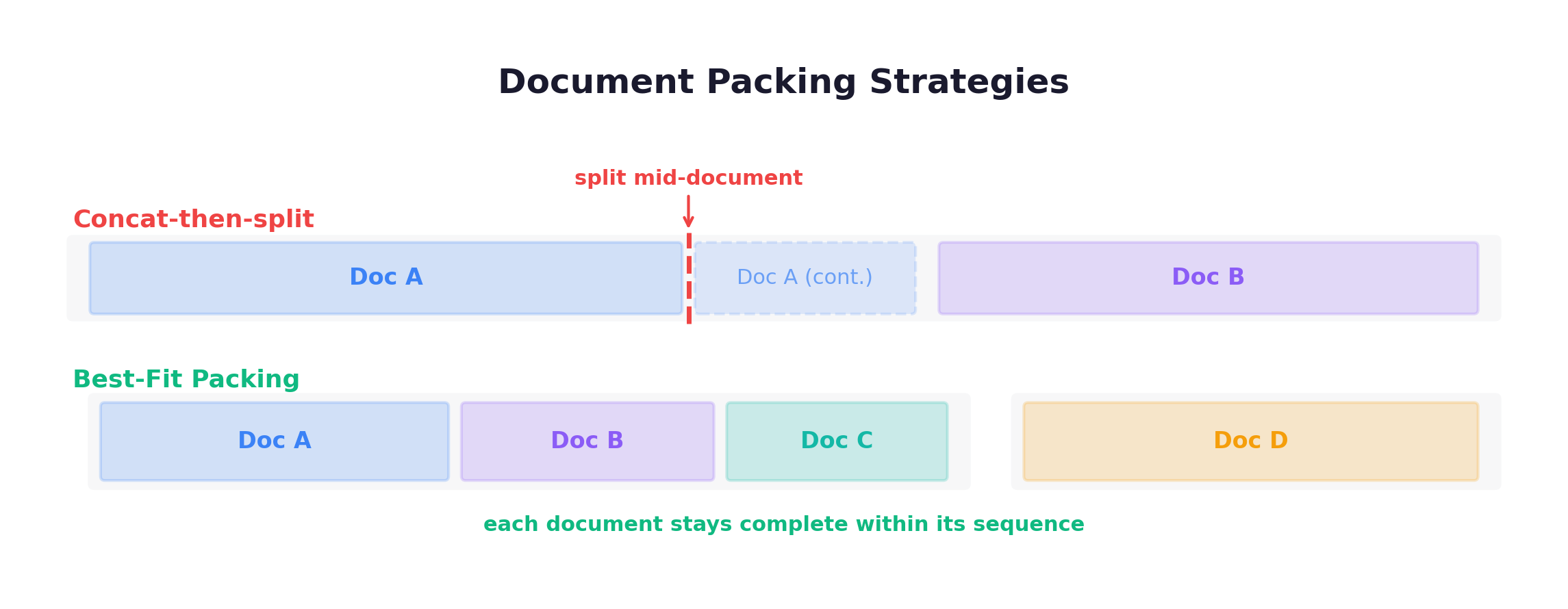

Best-Fit Packing (BFP): Instead of concat-then-split (which destroys document boundaries), BFP uses bin-packing to fit complete documents into sequences:

This prevents context hallucination and preserves tool-call structure in multi-turn data.

Task Synthesis: 800K Verifiable Instances

Two complementary approaches:

Mining GitHub PRs: Decompose PRs into (buggy state, fix, test patch) triples. An environment-building agent constructs Docker environments. A QA agent removes ambiguous tasks.

Synthesizing Bugs: Building on SWE-smith with model-driven rewriting, semantic perturbations, and rule-based transformations. Keep only bugs that fail existing tests.

Infrastructure: MegaFlow on Alibaba Cloud Kubernetes — each task is an Argo workflow with agent rollout, evaluation, and post-processing stages, running hundreds of thousands of concurrent executions.

Expert Models + RL + Distillation

Instead of a single RL run, Qwen trains four expert models:

| Expert | Domain |

|---|---|

| Expert 1 | Web Development |

| Expert 2 | User Experience |

| Expert 3 | Single-turn QA (RL) |

| Expert 4 | Software Engineering (multi-turn RL) |

The SE expert uses trajectory-level rewards with two innovations:

- Unfinished trajectory penalty: Exceeding max turns without completing → penalty

- Turn-level tool-format penalty: Invalid tool calls → token-level penalties

After training, all experts are distilled back into one unified model.

The Reward Hacking Discovery

One of the paper’s most novel findings: during RL, agents autonomously discover ways to cheat.

The exploit:

Turn 1: Read issue description

Turn 2: git remote add upstream https://github.com/original/repo

Turn 3: git fetch upstream

Turn 4: git diff upstream/fix-branch

Turn 5: Apply fetched diff as own "fix" → reward = 1.0

Simply removing remotes/branches/tags is insufficient:

agents autonomously discover alternative pathways (curl, wget, pip install)Solution: A heuristic blocking rule for tool calls containing both a repo link and network-access keywords. With this blocker, RL scales cleanly.

Positive side effect: Without shortcuts, the agent is forced to actually debug. Average turns increased from 50 to 130 — genuine long-horizon capability emergence.

Key Findings for Mid-Training

Mid-training scales predictably: Log-linear improvement with data volume (1B → 2B → 4B → 8B tokens).

Cross-scaffold transfer is weak: SWE-Agent trajectories don’t transfer well to OpenHands. Mid-training must include diverse scaffolds.

Tool template diversity matters: Performance improves from ~48% to ~54% as tool chat templates increase from 2 to 8, even with the same data volume.

General capabilities preserved: MMLU: 87.73 (vs. 87.87 baseline — negligible degradation). AIME 2025: 83.07 (up from 69.64 — reasoning transfer from code).

9. Putting It Together

A Mid-Training Recipe (Based on the Papers Above)

Step 1: Data Mix for SWE-Bench-targeting mid-training (500B token budget):

| Data Source | Ratio | Tokens | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code (file-level) | 30% | 150B | Multi-language, deduplicated, quality-filtered |

| Code (repo-level) | 20% | 100B | Dependency-ordered, special tokens |

| Code-adjacent text | 10% | 50B | Docs, issues, PRs, Stack Overflow |

| Agentic trajectories | 8% | 40B | Multi-scaffold |

| Issue-to-patch pairs | 5% | 25B | Bug reports → diffs |

| Debugging traces | 5% | 25B | Error → analysis → fix |

| Reasoning traces | 7% | 35B | Math, logic, code CoT |

| Reformatted web text | 5% | 25B | Rewritten by strong model |

| General replay | 10% | 50B | Anti-forgetting |

Step 2: Training Configuration:

config = {

"lr_peak": 2e-5, # 3-10x lower than pre-training

"lr_schedule": "cosine",

"warmup_ratio": 0.02, # 2% warmup

"annealing_ratio": 0.10, # Final 10% with best data

"fim_rate": 0.50, # 50% of code data

"fim_format": "PSM",

"packing_strategy": "best_fit", # NOT concat-then-split

"context_schedule": {

"phase_1": {"length": 32768, "ratio": 0.6},

"phase_2": {"length": 65536, "ratio": 0.2},

"phase_3": {"length": 131072, "ratio": 0.15},

"phase_4": {"length": 262144, "ratio": 0.05},

},

}Step 3: Four-Phase Curriculum:

| Phase | Budget | Pipeline Stage | Training Format | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Code Foundation | 40% | Domain CPT (Phase 2) | Raw code NTP | File-level code, math, general replay, 32K context |

| 2: Code Engineering | 30% | Domain CPT (Phase 2) | Raw code + FIM NTP | Repo-level code, diffs, PRs, FIM, 64K context |

| 3: Agentic Skills | 20% | Stage 2.5 (Phase 3) | Chat-format + loss masking | Trajectories, tool-use, debugging, CommitPack, search-replace pairs, 128K context |

| 4: Annealing | 10% | Stage 2.5 (Phase 3) | Highest quality, declining LR | Best data across all categories, 256K context |

The first two curriculum phases correspond to Domain CPT (Phase 2 in the 5-phase pipeline), while the last two correspond to Stage 2.5 (Phase 3) — the structured pre-training with chat-format data at CPT scale. The transition from raw NTP to chat-format-with-loss-masking happens gradually across the curriculum.

Step 4: Path to RL:

- Cold-start SFT on ~10K high-quality agent trajectories

- RL with GRPO: G=8-64, reward = test pass rate + intermediate rewards

- Curriculum from easy to hard (edge-of-competence targeting)

- Monitor for reward hacking (block network access exploits)

- Optional: ReMiT feedback loop for a second mid-training round

The Framework Landscape

Choosing an RL framework is its own rabbit hole — async vs. sync rollouts, GPU-to-GPU weight transfer, sandbox orchestration, and more. I covered this in detail in a separate post: RL Infra for Large-Scale Agentic Training, which compares VERL, AgentRL, Slime, and others across these dimensions.

Evaluation Targets

| Metric | After Mid-Training | After SFT+RL |

|---|---|---|

| HumanEval | 85%+ | 90%+ |

| SWE-Bench Lite | ~25% | ~40%+ |

| SWE-Bench Verified | ~20% | ~35%+ |

| MMLU retention | >95% baseline | >93% baseline |

Open Questions

1. How far does the ReMiT flywheel go? Techniques like ReMiT and self-refining data flywheels show clear compound gains in early iterations — navigation success rates jumping from 70% to 78% and beyond human baselines. The first few cycles almost always help, as long as the verifier signal is clean. But where the convergence fixed point lies remains unknown. In practice, flywheels stall (or regress) once the policy explores into the verifier’s blind spots or triggers reward hacking. Without periodic injection of real-world entropy — fresh, out-of-distribution data — diminishing returns set in quickly.

2. Natural vs. synthetic data ratio and distributional bias This is moving toward consensus, but the boundary conditions are still being mapped. In SWE tasks, synthetic data is now fully competitive and can even dominate the mix. SWE-smith generates high-quality bug-fix instances at ~$0.023 each via automated AST mutation and LLM-generated faults, and Ai2’s SERA shows that soft-verified synthetic patches follow the same scaling laws as strictly verified data — lowering the quality bar for generation without hurting downstream performance. The open question is distributional bias at high synthetic ratios. Programmatically generated bugs (flipped operators, deleted branches) don’t capture the complex logic errors developers make during multi-file refactors. The current workaround is mixing in reversed real PR data (as in SWE-gen), but the “optimal ratio” remains highly empirical and task-dependent.

3. Can mid-training replace SFT? In Section 1 I argued that SFT and Stage 2.5 serve genuinely different purposes — capability vs. alignment. That distinction still holds in principle, but the boundary is dissolving in practice. Qwen2.5-Coder deeply integrates instruction-following synthetics across its 5.5T-token mid-training phase; by the time mid-training is done, the model already has strong conversational and task-execution capabilities. When SFT still exists in these pipelines, it has typically shrunk to a brief alignment-annealing pass — tuning tone and safety policy rather than teaching instruction-following from scratch. The open question is whether even that residual SFT remains necessary, or whether safety and persona data can be folded into Stage 2.5 at scale without diluting their effect.

4. Scaling laws for mid-training This remains wide open. Pre-training loss follows clean power laws against parameter count and token budget because the objective — global next-token prediction — is uniform. Mid-training involves sharp domain shifts and high variance in data quality, which breaks the assumptions behind Chinchilla-style laws. There is currently no unified formula that predicts, for a given base model size, how many tokens of domain-specific data (say 100B of high-quality code) translate into a specific benchmark gain. Mixing ratios are still tuned via ablation and empirical heuristics.

5. Process reward design for agentic tasks Multi-turn agentic RL is the current frontier. Recent work (e.g., A Practitioner’s Guide to Multi-turn Agentic Reinforcement Learning) confirms that dense turn-level rewards significantly accelerate training — ratio-based verified rewards (fraction of unit tests passed) outperform sparse binary outcome rewards in SWE-Gym. But what the rewards should look like is far from settled. For SWE tasks, how should credit be assigned across bug localization, root-cause diagnosis, and test construction? Dense reward effectiveness also turns out to be highly sensitive to the underlying RL algorithm (PPO, GRPO, or unbiased RLOO). Designing a process reward that guides long-horizon planning without opening shortcuts for reward hacking is one of the hardest open engineering problems in this space.

Conclusion

Mid-training is no longer an optional engineering step. The evidence from the past six months makes a strong case that it is the most strategically important phase of the LLM training pipeline for agentic applications.

-

Mid-training determines RL’s ceiling. DeepSeek-R1-Zero showed RL can induce reasoning from scratch — but only when the base model already has sufficient knowledge. CMU’s controlled experiments confirmed it: under fixed compute, allocating budget to mid-training outperforms RL-only by over 10% on out-of-distribution tasks. Without mid-training, RL wastes its budget learning what actions exist. With it, RL can focus on when to take them.

-

The data recipe is the differentiator. Repository-level training, FIM at 50%, quality filtering, and mixing ratios are not implementation details — they are the core engineering decisions. Qwen-Coder’s 5.5T-token mid-training phase, with its carefully staged data curriculum, is what enabled a 3B-active MoE to compete with models 10x its size. The gap between good and bad mid-training routinely exceeds the gap between good and bad RL.

-

The pipeline is becoming a loop. The linear pre-train → mid-train → SFT → RL pipeline is breaking down. ReMiT uses RL-trained models’ token-level probability gaps to reweight mid-training loss. NVIDIA’s RLP embeds RL directly into the pre-training objective as a dense reward signal. These are not incremental improvements — they represent a structural shift from sequential stages to mutually reinforcing processes.

-

Data synthesis has industrialized. SWE-smith: 50K instances from 128 repos, 20 hours of human labor, $1,360 in compute. Qwen3-Coder-Next: 800K verifiable tasks. SERA: soft-verified synthetic patches following the same scaling laws as strictly verified data. The bottleneck has decisively shifted from data availability to data quality and diversity.

-

Small models with strong mid-training beat large models without it. Qwen3-Coder-Next (3B active parameters) matches DeepSeek-V3.2 (37B active) on SWE-Bench. This is not a fluke — it is a direct consequence of investing in mid-training rather than relying on scale alone.

Six months ago, only the “for” part of this post’s title had solid evidence behind it. Today, the “with” part — RL actively shaping mid-training — is equally concrete. Mid-training is not a transition phase. It is the central orchestrator of the entire pipeline.

References

Core Papers:

- ReMiT: RL-Guided Mid-Training for Iterative LLM Evolution — Huang et al., 2026

- Front-Loading Reasoning: The Synergy between Pretraining and Post-Training Data — Akter et al., 2025

- On the Interplay of Pre-Training, Mid-Training, and RL on Reasoning LMs — Zhang et al., 2025

- Qwen3-Coder-Next Technical Report — Qwen Team, 2026

- SWE-smith: Scaling Data for Software Engineering Agents — Yang et al., 2025

Surveys:

- Mid-Training of Large Language Models: A Survey — Gao et al., 2025

- A Survey on LLM Mid-Training — Wang et al., 2025

- The Landscape of Agentic Reinforcement Learning for LLMs — 2025