Why Infrastructure Is the Real Bottleneck

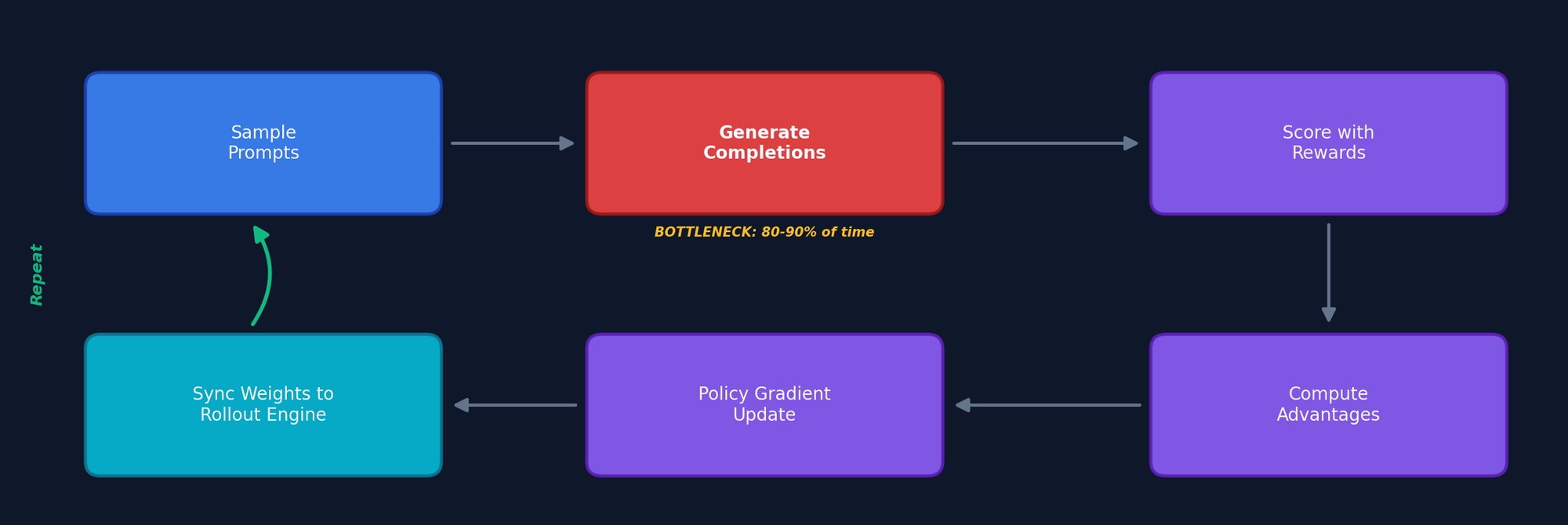

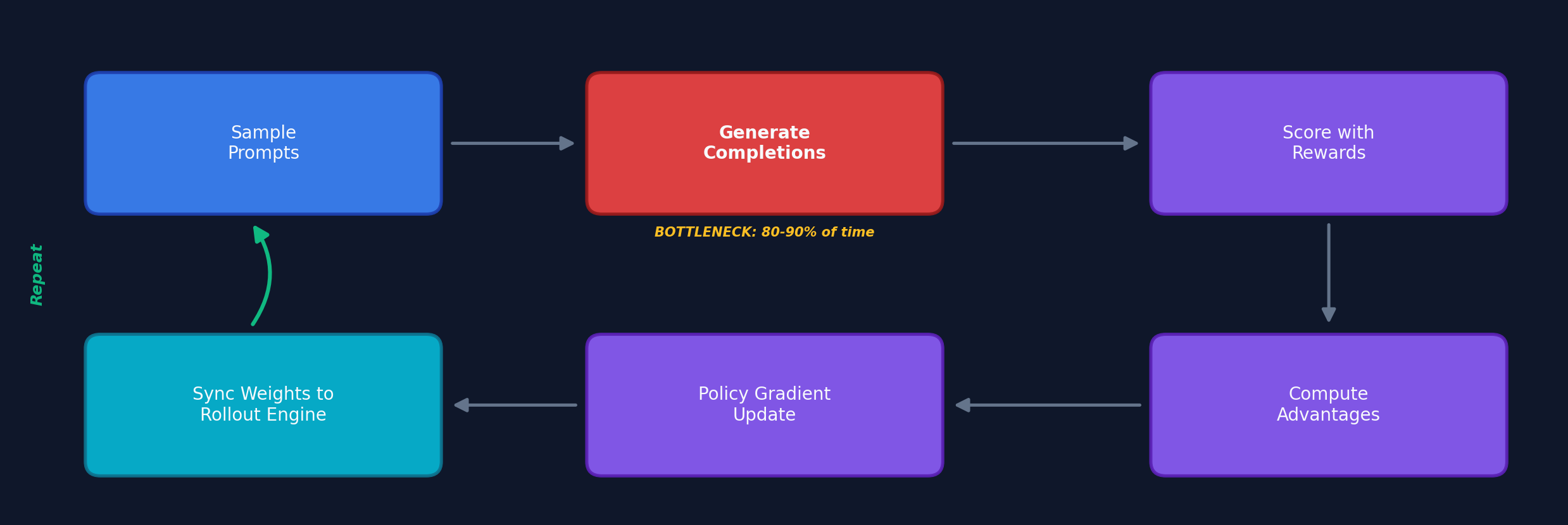

The recipe for training reasoning models with RLVR is conceptually simple: generate solutions, verify correctness, update the policy with policy gradients. But at scale, 80–90% of training time is spent on sample generation, not on the policy update itself. Infrastructure — not your loss function — is the primary constraint on experiment throughput.

This matters for algorithm researchers because:

- GRPO eliminates the critic partly because fitting it alongside the policy is an infrastructure pain point

- DAPO’s dynamic sampling only works if your framework handles variable batch sizes

- Two implementations of “the same algorithm” produce different results based on padding vs. packing, sync vs. async weight updates, and inference engine choice

Understanding the infrastructure is not optional — it’s a prerequisite for effective RL research.

Anatomy of the RL Training Loop

Every RL training system involves up to five model roles:

| Role | Purpose | Memory (7B, bf16) |

|---|---|---|

| Actor | Policy being trained | ~84 GB (weights + optimizer + gradients) |

| Rollout | Fast autoregressive generation | ~14 GB (weights) + ~40 GB (KV cache) |

| Reference | Frozen copy for KL divergence | ~14 GB (weights only) |

| Critic | Value function (PPO only) | ~84 GB (training memory) |

| Reward | Score completions | Variable |

The training iteration cycle:

PPO requires all five roles (4 models on GPU). GRPO eliminates the critic but needs G completions per prompt (typically G=4–16). DAPO adds dynamic sampling (variable batch sizes), token-level loss, and overlong reward shaping (max 20K tokens). These algorithmic choices have direct infrastructure implications: memory footprints, generation volumes, and batch handling requirements.

Environments: From Milliseconds to Hours

As we move from simple math verification toward agentic RL, environments become the infrastructure challenge:

Simple verifiers (math answer checking) take milliseconds and run on CPU. Code sandboxes require isolated containers with dependencies, taking seconds to minutes. Full agent environments (SWE-bench, research tasks) can run for minutes to hours with GPU access.

Poolside’s RLCEF: The Industry Reference

Poolside’s code execution environment represents the state of the art:

- 800,000+ repositories indexed and containerized as OCI images

- Saucer service: gRPC-based repository hosting with Git packfile indexing for random access at any revision

- OverlayFS layering: Thin delta layers per revision avoid quadratic storage growth

- Task Engine: Orchestrates millions of concurrent code executions for online RL

- AI-agent-based building: Factory-trained agents help build complex C++ containers — a self-improving loop

MiniMax’s Scale

MiniMax built a sandbox infrastructure launching 5,000+ isolated environments within 10 seconds, supporting tens of thousands of concurrent executions across 10+ languages, sourced from 100,000+ real GitHub repositories with Issues, code, and test cases.

The Long-Tail Problem

In agentic RL, episode lengths follow a heavy-tailed distribution: 40% of tasks complete in under 30 seconds, but 10% take over 10 minutes. With synchronous training, the entire batch waits for the slowest episode, leaving fast-completing GPUs idle. This drives the need for asynchronous architectures.

The Architecture Spectrum: Sync to Fully Async

Level 0: Fully Synchronous

Generate all → Score all → Train → Sync weights → Repeat. Simple but suffers from head-of-line blocking. Acceptable for uniform-latency tasks (math RLVR).

Level 1: One-Step Off-Policy

Overlap current training with next generation. Rollout uses weights from the previous step. VERL reports 2.35–2.67× improvement on 128 GPUs.

Level 2: Request-Level Async

Each conversation progresses independently. No batch barriers. Essential for agentic RL: without this, one conversation needing a 5-minute tool call blocks all GPUs.

Level 3: Fully Asynchronous

Generation and training proceed independently on separate GPU pools. AReaL reports 2.77× speedup vs synchronous. Requires staleness management.

Engine Mode vs. Server Mode

Engine mode (in-process inference): all requests must complete before any can proceed. Server mode (HTTP/RPC service): each request independent, supports dynamic batching. The trend is clear — VERL v0.7 switched to server mode as default. Slime has always used server mode. Server mode is becoming the standard for agentic RL.

Slime’s Inverted Design: A Paradigm Shift

Slime, the SGLang-native framework behind GLM-4.5/4.6/4.7, introduces a fundamental architectural inversion.

Traditional: Framework Controls the Environment

class Framework:

def rollout(self, prompt):

response = self.generate(prompt)

tool_result = self.call_tool(response) # Framework manages this

response2 = self.generate(prompt + tool_result)

return self.compute_reward(response2)

Every new environment type requires modifying the framework’s rollout logic. Bloated, brittle, meets only a fraction of real-world needs.

Slime: Environment Calls the Framework

class AgentEnvironment:

def init(self):

self.client = OpenAI(base_url=“http://sgl-router:8000/v1”)

def run_episode(self, task):

messages = [{“role”: “user”, “content”: task}]

for turn in range(max_turns):

response = self.client.chat.completions.create(

model=“policy”, messages=messages

)

# Environment handles its own logic

if needs_tool_call(response):

result = self.execute_tool(response)

messages.extend([assistant_msg, tool_result_msg])

else:

return self.compute_reward(messages)

The environment doesn’t know it’s talking to a training system. It uses the same OpenAI-compatible API it would use in production. This gives:

- Zero environment modification: Any existing agent works with Slime during training

- Training-deployment consistency: Same API in training and production

- Lightweight framework: Slime doesn’t need to understand environments

Slime’s three components — Training Engine (Megatron-LM with 5D parallelism), Rollout Engine (SGLang + sgl-router), and Data Buffer — communicate through clean interfaces. Custom rollout logic is injected via --rollout-function-path, not framework subclassing.

Production results: GLM-4.5 (355B/32B MoE) achieved 70.1% TAU-Bench, 91.0% AIME 2024, 64.2% SWE-bench Verified. APRIL integration provides up to 44% throughput improvement for long-tail distributions.

GPU-to-GPU Weight Transfer: The Hidden Bottleneck

After each training step, updated weights must reach the inference engine. For large models, this transfer is a significant fraction of iteration time.

The Challenge

Training (Megatron: TP=4, PP=2, EP=8) and inference (SGLang: TP=8, DP=4) use different parallelism layouts. Weights must be gathered from the training topology and redistributed into the inference topology — a resharding operation.

Mechanisms Compared

| Framework | Mechanism | Speed | Key Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slime | CUDA IPC zero-copy | 7s (30B, 8×H100) | Tensor flattening + bucketing reduced IPC overhead from 81% to 16% |

| VERL | 3D-HybridEngine resharding | ~10-15s (est.) | In-place parallel regrouping; Checkpoint Engine (v0.7): 60%+ reduction |

| Poolside | GPU-Direct NCCL | ~2s (405B, P5e nodes) | 3200 Gbps EFAv3 + GPUDirect RDMA; fully async |

| TorchForge | TorchStore RDMA KV | TBD | Distributed in-memory store on Monarch; weight versioning |

| MoonshotAI | Checkpoint-Engine | ~20s (1T, 256×H20) | Three-stage pipeline: H2D → Broadcast → Reload |

Poolside’s GPU-to-GPU transfer achieves the fastest reported speed: Llama 405B (810 GB in bf16) in ~2 seconds on P5e nodes, running fully asynchronously while training continues. However, they note significant engineering challenges: exact NCCL version matching across all nodes, deadlocks from mismatched send/recv order, and non-deterministic failures at scale.

The future direction is DDMA (Distributed Direct Memory Access): GPU↔GPU over NVLink/InfiniBand with zero CPU involvement, eliminating the host bottleneck entirely.

Framework Comparison

| Dimension | VERL | Slime | TorchForge | OpenRLHF | MiniMax Forge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | FSDP / Megatron | Megatron / FSDP | torchtitan | DeepSpeed / Megatron | Internal |

| Inference | vLLM / SGLang | SGLang (native) | vLLM | vLLM | Internal + SGLang |

| Orchestration | Ray | Ray | Monarch | Ray | Internal |

| Weight Sync | In-process / Checkpoint Engine | CUDA IPC / Distributed | TorchStore (RDMA) | NCCL broadcast | Internal |

| Agentic RL | VerlTool + AgentLoop | Native (inverted design) | OpenEnv | Agent paradigm | Black-box agents |

| Scale | 671B (DeepSeek-V3) | 355B (GLM-4.5 MoE) | 512 GPUs tested | Mature community | 512 H800 GPUs |

| Maturity | Production (most mature OSS) | Production | Experimental | Production | Production (internal) |

When to Choose What

- Algorithm prototyping: TorchForge (pseudocode-level APIs) or VERL (mature, many algorithms implemented)

- Production agentic RL: Slime (inverted design, zero env modification) or VERL (VerlTool, large community)

- PyTorch ecosystem: TorchForge (Monarch + torchtitan + vLLM, all PyTorch-native)

- Large MoE models: Slime or VERL with Megatron (both support 5D parallelism + EP)

- Easiest onboarding: OpenRLHF (designed for ease of use)

Algorithmic Innovation from MiniMax

MiniMax’s CISPO (Clipped Importance Sampling Policy Optimization) takes a different approach to the clip-ratio problem: instead of clipping the surrogate objective (PPO) or using direct advantage optimization (DAPO), CISPO clips the importance sampling weights themselves while preserving gradient updates for all tokens. This achieves 2× speedup over DAPO in controlled studies and was used to train MiniMax-M1 on 512 H800 GPUs in 3 weeks.

Scaling to Production: Lessons from Poolside

Poolside’s Model Factory — a 10K H200 GPU cluster with Dagster orchestration, Apache Iceberg data lake, and fully automated experiment management — offers key lessons:

-

Decouple everything: Subsystems must be independently modifiable. When you upgrade your inference engine, training shouldn’t break.

-

Configuration as code: All experiments specified declaratively. Scheduling a new sweep takes <10 minutes. Full reproducibility via versioned Dagster assets.

-

Stream, don’t materialize: Data streamed into training via Blender, not pre-materialized. Data mixes changeable live during training.

-

Evaluate early and often: Evaluations every 100–1000 steps, not just at the end. Multiple benchmarks, run automatically, track regression.

-

Automate failure recovery: Pre-flight node stress tests → automatic isolation → automatic replacement → automatic restart → engineer escalation only as last resort.

-

Build self-improvement loops: Use your own models to improve your infrastructure. Poolside’s Factory-trained agents improve the Factory.

The Road Ahead

The RL infrastructure landscape is converging on several trends:

- Server mode as default: The inference engine runs as a service, not an in-process library

- Standardized environments: OpenEnv (Meta + Hugging Face) pushing Gym-style

step()/reset()/state()for all RL environments - Training-serving convergence: The same engine used during RL training is the production serving engine

- GPU-direct transfers: Eliminating CPU bottlenecks in weight synchronization

- Cross-provider heterogeneous training: Training on one cloud, inference on another

The gap between what’s possible with state-of-the-art infrastructure and what most researchers actually use is enormous. The frameworks are evolving rapidly — VERL, Slime, and TorchForge each release major updates monthly. But the core principles remain:

Generation is the bottleneck. Async is essential for agentic RL. Weight sync speed determines iteration time. Decouple your components. Let environments drive the loop.

Closing the infrastructure gap is the fastest way to accelerate RL research.

References

- Poolside Model Factory Blog Series (6 parts)

- Slime: SGLang-Native Post-Training Framework (LMSYS Blog)

- VERL: HybridFlow Paper (EuroSys 2025)

- TorchForge: PyTorch Blog

- Anatomy of RL Frameworks (Hanifleo)

- When LLMs Grow Hands and Feet: Agentic RL Systems (Amber Li)

- MiniMax-M1 Technical Report

- APRIL: Active Partial Rollouts in RL

- VerlTool: Agentic RL with Tool Use

- Open Source RL Libraries for LLMs (Anyscale)

- OpenEnv: Building the Open Agent Ecosystem (Hugging Face)

- GLM-4.5 Technical Report